createid Collection, Season One

Season 1 Episode 9 | 42m 12sVideo has Closed Captions

Some of the most popular pieces from the first season of createid.

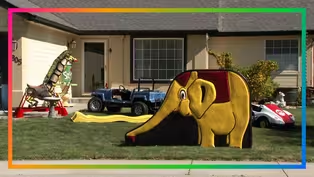

From architecture to dance, the createid Collection is a compilation of some of the most popular pieces of the first season of createid, a series focusing on the arts in Idaho.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

createid is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding provided by the Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

createid Collection, Season One

Season 1 Episode 9 | 42m 12sVideo has Closed Captions

From architecture to dance, the createid Collection is a compilation of some of the most popular pieces of the first season of createid, a series focusing on the arts in Idaho.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch createid

createid is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

createid on YouTube

createid celebrates the unique talents of Idaho creators through lively video pieces. See exclusive content and join the community on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube. Subscribe now!Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMajor funding for “createid” is provided by the Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

(MUSIC) Hi, I'm Marcia Franklin in front of the JUMP building in Boise, Idaho.

This unique structure houses multiple studios, all dedicated to celebrating creativity, from choreography to woodworking to invention.

Humans are innately imaginative, and that wellspring of creativity bubbles up in a myriad of ways.

Our new series, “createid,” showcases that ingenuity.

In our inaugural episode, we're excited to share stories from around Idaho about talented creatives.

Our first two pieces highlight individuals who are keeping traditional arts alive while adding their own unique touches.

[man chanting in Greek] Kordis: You have to have a connection with what you paint.

I don't think that you can render the deep spirit of the work if you are not close to that.

For me, this is my, I would say, mother artistic language.

[music] Father Zosos: When we were in the renovation, I felt, “Why not put icons in it that never had any for a hundred years?” It's bringing the historic tradition to the present.

[music] Rockwood: It isn't just a picture.

They tell a story.

They help us understand things.

They don't make things up and paint it on the wall.

It's things that we actually understand from years way back that actually occurred.

Zosos: The souls of these individuals are still alive, as our souls are.

So there is a relationship.

We just don't look at them.

We pray to them.

We ask them for their intercessions.

Kordis: It's a very old technique.

And the idea is that we mix a medium and pigments, which are basically oxides, different oxides.

And this way we create a paint.

We want to have a very simple palette, so when you enter the space, these colors to be peaceful and reconciled, and in unity.

It is a complete system of painting.

I would say perfect system.

Panou: Every time is different.

Every church is different.

You have to study and work and persist.

We all do everything in this group, but I usually make like the ornaments and all the small details around.

It's like calligraphy, actually.

That's why I like it.

Yes.

I have this really bad habit to put every color on me, just dry my brushes on me.

It's not very practical.

[laughs] I have tried so much to stop it.

And then I do it again and again.

[laughs] It's my style.

Yes.

I have to accept it.

[laughs] [music] Goodner: It's very moving.

It's very moving.

It's amazing how fast they're doing this and how beautiful it is.

It's stunning.

All of these saints, they're people.

And I feel like they're friends and they're helping me.

Zosos: It takes you a little while sometimes to appreciate them because their faces are different, their hands are different.

But that's because they've elevated themselves; they've grown closer to God, to a place that we can't understand right now.

Kordis: Smiling or joy or sorrow is something that is temporary.

That - it's not there forever.

So we, we try to render such things through movement.

The depth in Byzantine painting is in front of the icon, it's not in the background.

We want through this painting to give spectators the sense that everything is here in present.

If you have a movement towards this direction, then you have immediately another movement to the other direction.

This way, actually painter creates a cone, a visual, iconic cone in front of the icon So when the spectator enters this cone, has the sense that he's inside the icon.

Wherever you stand, he's looking at you.

And if you move, he is following you.

In every church, the most interesting and difficult part definitely is the icon of Jesus in the dome, which is sometimes - it's very big, very huge and very difficult to handle because it's a big artwork.

We are very close.

Rockwood: People came forth with all of the money that it took to do this.

[Greek music] Zosos: Our biggest fundraiser has been the Greek festival.

It's one of the largest, well-attended events in the summer.

[chanting] Iconography has existed from the beginning of the Christian church.

In the early church, they used to use the yolk of an egg with powder paint to do this.

It█s laborious work.

There's like three or four or five different levels of paint that go on this.

And it's beautiful.

When you enter an Orthodox church and you come from the secular world outside and the door closes behind you, you know you're in the presence of God.

You know that it's special.

Help us, save us, have mercy upon us and keep us, O God, in your grace.

[audience responds] Goodner: This is the way it should be.

When you walk into an Orthodox church, you should feel this communion of saints and ordinary people today and the feeling of history.

Kordis: We hope that they will be inspired.

They will be able to pray better or more in this peaceful space.

[bell ringing] Zosos: I have to tell you, it brings tears to my eyes.

I get emotional because, you know, as you get older I think you want to get closer to God.

And this surely is a way of doing that.

[singing and bell ringing] [Music] My name is Hooey.

I braid leather.

It's over 50 years I've been doing what I'm doing.

It, it took me a long time to get competent at it, and then it took even longer than that to get to the level I'm happy with.

I can't keep up with the demand during the busy season.

I went completely traditional.

In the 1800s that's what they had to work with.

And this is what they did.

The hat band kept the hat in shape.

Part of what makes my work a little different, I've put some nautical work into leather work.

The braided knots, the pineapple knot, that's my signature right there.

Who I sell to people that take pride in their work and hand-build a hat.

They build the hat to fit your head.

And somebody that's going to go through that, they're not going to want a second-class hatband.

Kangaroo leather happens to be the best for braiding purposes.

Nothing else even comes close.

That kangaroo leather will retain more strength and last longer than any other leather out there.

It's circle-cut.

You don't just cut strips.

The advantage to this, you can get long lengths.

If you were to cut this way, you would get, uh, 14-15 inches.

If you string-cut an entire hide could get over 200 feet in one single string.

Now we move over to phase two.

I whittle it down.

Tiny fractions of an inch to give me the perfect dimensions that I'm after.

Okay, now I measure this.

128th of an inch is what I've taken off.

That's a shaving.

We█re going to recut the edges and put a bevel into the edges.

It allows your braid to lay in instead of lay on.

And this starts the actual braiding.

Here█s where the beveling shows.

It takes the edge off everything.

My pineapple knot is what I enjoy the most.

Very few people tie those anymore.

Very few people know how to tie those anymore.

It's a interwoven knot.

You start out with a knot that's called a Turk's head.

It's tied very loosely and put in place.

And then the tightening process.

When you tighten a Turk█s head, it's not like a boot lace.

You don't just pull the ends and expect it to tighten.

You take a little bit of slack out.

You form your knots.

You don't just tighten them.

And then you weave another Turk's Head into that first Turk█s Head.

If you tuck it wrong in any place along the way, nothing else will come out right And I think it's a beautiful knot.

Okay.

At this point, it's completed.

And you can adjust it to a perfect fit for just about any hat made.

It's a culture, a tradition.

You go in any store now, everything you buy was made by a machine.

Everything is mass-produced and disposable.

When they buy something of mine, it's made to last.

It's made the traditional way and it's made with care.

And I take pride in my work Everybody can do something well in life.

Something makes you happy.

And I was lucky.

A long time ago I knew what made me happy and I could do well.

And I'm still doing it.

Some creatives draw their inspiration from art forms that are centuries old, but reimagine them to incorporate their own history and identity.

One such artist is Lupe Galv á n. Creativity is the thing that sort of animates us.

I think it's essential.

It’s so essential that if I don't have something to do that feels creative, then I feel like I'm not being, you know, my human self.

My name is Lupe Galván and I am a painter.

My father's family is from Mexico.

They're from Guadalajara.

My mother's background is, is Huichol.

Huichol people are an indigenous group in Mexico.

I grew up doing farm work.

And it was really, really hard.

I remember really, really being very upset that I had to do it.

Growing up, art was something that I came across via my sister, who had a sketchbook.

And I remember asking her what she was doing and she was like, “I'm drawing” And I said, “Can I look?” And I was, it was like magic, because she was just like, so many different things.

And I was like, “I want to do that!” And then later, when she went to college, she gave me an art history book.

And I just, I was in disbelief.

I was like, “Oh my God, what is this?” And I would keep it next to the bed and, you know, just look at it and look at it.

And I would imagine I was at the top of the hill, you know, and instead of working, I was actually outside doing plein air paintings.

And it was just like, this little world that I had created for myself unknowingly.

I saw an opportunity that if I could go to an art school, um, then I would take it.

I applied at the New York Academy of Art, got a scholarship.

And I was like, “Wow, this is going to change my life.” So this is a painting that's inspired by Titian's “Bacchus and Ariadne.” I love Titian paintings.

And I guess in some ways I wanted to make it my own.

And the painting is called “Ancestors.” In the Titian painting, Ariadne is abandoned on an island, and Bacchus sees her and immediately, you know, falls in love with her.

But I wanted to retell the story.

In some ways, it's like the story of what I imagine was happening with my ancestors.

And so they're engaged in this dance, a kind of, like, perpetual dance of time.

The figure is representative of my mom or my grandmother.

Because to me, the idea, the notion of a matriarchy is, like, is a very important element.

I mean, it's kind of how I grew up.

And most indigenous cultures were matriarchies.

If you look at her feet, you know, they're like, powerful, very strong feet.

They're almost like roots, you know, the, they█re the people of the land.

The idea of ancestry is that there was another me at some point.

I'm striking a pose that isn't exactly a masculine pose.

I love the idea that masculinity can be a little bit vulnerable.

There is a skeleton.

And that is an homage to the European “vanitas,” which is a constant reminder of, you know, death being around the corner.

It is also representative of genocide that occurred in a lot of the untold stories of the colonization of the Americas.

This is a clay dog that is known as a xoloitzcuintle, which is a Mesoamerican, uh, hairless dog.

And then the hare represents the scribe in sort of Mesoamerican culture.

So he is the one who records what is happening, but he cannot intervene.

And then there's, uh, an effigy that's being burned.

It is an homage to José Clemente Orozco.

So Orozco did a painting that was called “The Man of Fire.” He represents a new race that's going to be born out of chaos.

Where people were going to cast their notions of race and nationality into the fires.

The way that I work is I use a tablet, and I look for images.

Like if I was a director, who do I want to play the part of the hare or the dog?

When a painting is going well, uh, it makes me feel great.

There can be a huge time span where I forget to eat or, you know, I forgot everything else that was happening.

When it's not going so well, then I feel, then I feel like a failure, and I question, um, “Why did I do painting?” So a lot has changed.

And one of those things is building an addition to a house that we bought, and getting married.

So the painting was pretty much in storage.

In the previous segment, the woman had not been fully realized.

Since this painting is really essentially a love story, I wanted her turned more, so that you can at least see, you know, an idea that there's an engagement there.

I changed the clothing.

I wanted this to have, like, more of a natural look.

I think of myself as, you know, a byproduct of how I grew up, but also simultaneously having a love for European painting.

I don't have to praise all of the horrible things that happened under the regime of Europe and European art.

But they did do amazing things.

They did do beautiful things.

I think some of those stories are beautiful, too.

And the question I'm asking is, “Are our stories not beautiful as well?” Buildings like JUMP make a statement with their architecture.

They stand out, sparking conversation and even debate.

Other buildings are designed to blend seamlessly into the environment.

In our next piece from North Idaho, we meet a man who was a master of what is known as “Organic Architecture.” You just take one look at the house and you know this is special.

These are the original blueprints.

This to me is just a stunning amount of detail, and I know that this was his dream to build this.

So that's Unicorn Farm.

It has a kind of a magical quality about it.

I am Joseph Henry Wythe.

I█m an architect.

Been at this, uh, 70-some odd years now.

Lois said, “Well, I'll go up and I'll look around for our ideal property where we can build our dream house.” Well, we wanted property on the water because we want to watch the wildlife come down to the water.

We didn█t want to advertise that we're setting up a wildlife sanctuary.

Real estate agent asked her “What kind of property you want?” she said, “Well, we want a rural property where we can do some farming.” “Uh, what are you going to grow on a farm?” Lois dodged the question.

And so he kept coming back to it, and she finally got exasperated.

And she says, “I█ll tell you what, we're going to raise unicorns.” So when Lois called back that night, she says, “I haven't found our property, but I know what we're going to call it.” This is a house that's related to Frank Lloyd Wright and one of his followers by the name of Bruce Goff.

Mr. Wythe, who built his house, was his student and continued on the rest of his life as a person that was environmentally acute, and wanted to do architecture that was unique to its site rather than just another box.

This house is part of a kind of architecture that is often called “Organic Architecture.” And that are organicness means that it's related to the earth and site-specific.

But the fact that it has an earthen roof is very, very unique, because most organic houses were not earth-assisted.

so the name ‘Unicorn█ really works here, because there are about as many of these kinds of houses as there are unicorns.

You see the front entrance as you're coming down the driveway.

But even there, you know, you don't see it immediately.

As you come in, you█re, you enter a kind of an enchanted forest.

This road bends around so you don't see very far into that forest.

And so this winding through the forest instead of a straight line up to the front door, is unusual.

In an organic house, you don't enter all at once.

As you go down the hallway, you're intrigued to see what's around the bend.

And so this continuous experience of changing the views as you come through the house, it creates this feeling that you want to see more of it.

Explore.

Well, what are the beauties of this space?

That's what makes it organic, because you and the building are reacting together.

I knew that we wanted the opening towards the south.

It could be dug into the side so we could do an Earth shelter house.

We need an outside living space, a screened porch that was accessible to the main living space.

The idea of a Great Room, uh, appealed to me.

They all could converse back and forth between the various areas.

And the fireplace is where it can be seen from all three areas.

So that was the basic concept.

And then, so it came, it came together rather quickly.

And from that, uh, I saw that they were arranged at a, a 45-degree angle from the basic outside.

So the house wound up, uh, based on an angle of multiples of 22- and-a-half degrees.

22-and-a-half, 45, on up to 90 and 180 degrees.

So as you look at the floorplan of this house, you can see those multiple angles coming into play.

Just worked out very beautifully.

Before we saw it, we knew nothing about it.

We didn't know it existed.

We decided that if we didn't try to buy it we█d regret it forever.

And here we are, uh, we bought it in 2020.

And it's now 2023 and we're still learning things about the place.

It's pretty fascinating.

It's, uh, peaceful.

It's quiet.

Every season, you get a different view out the same window.

I think Mr. Wythe, as he aged, he just couldn't keep up with the place, There was anything wrong with the place; it had just been neglected.

We did some tree removal, tore everything off those banks in front of the house, opened up a lot of spaces.

The biggest thing of the roof, by far.

And we knew it leaked when we bought the house.

When we found that the seams were the problem, that was actually a blessing, because it became very easy to fix.

So all we've had to do now is reseal all the seams, and everywhere we've done that, the leaks have stopped.

These creative houses have a hard time living in the modern world, because it's hard to find people to take care of them.

You have to work hard.

I think Christopher has been pretty creative about taking care of this house.

I█m not a builder.

I'm not a contractor.

You know, I█m an accountant who happens to think he's good at stuff and, um, can follow directions, but it's been a lot of fun.

A lady came through this house one time and she says, “You know, this, this house feels like it loves me.

It feels like it's wrapping its arms around me and giving me a great big hug.” It's a pretty special place.

Feel pretty darn fortunate be living here.

A very special dance group often uses this studio.

Come with us as we follow the Open Arms Dance Project as it rehearses for one of its biggest performances ever.

[Music] I love dance.

I just love the ability you have to express yourself through movement.

Because a lot of times with me, it's hard.

I live with cerebral palsy.

And when I was in school, kids were very mean to me.

If I was coming down the hall they would call me "penguin."

It's hard for me to express my emotions, and when I'm dancing, I can really do that and feel free to do that, and not feel like I'm being judged or someone's going to say something negative to me.

My name is Heather Marie, and I am an Open Arms dancer and ambassador.

I'm Gail Chandler Hawkins, and I am a dancer with Open Arms Dance Project.

What we do is adapt.

It's okay if you can't do it quite this way, then do it this way.

So Reema and Haya, you'll come on.

We do the toes and heels...

I'm Megan Brandel, and I'm the founding artistic director of Open Arms Dance Project.

I put really ordinary people on stage doing really extraordinary things.

I take anybody in Open Arms.

They don't have to have any dance training.

They don't even have to be able to walk.

And so that really flips the script and says, "Look closer and see the beauty in these people."

I think that representation on stage is key because that is usually not centered and highlighted and spotlighted in the performing arts.

So my dad was the one who always danced with me.

He was the one with rhythm and the one I would two-step with.

He was physically losing movement one limb at a time.

And so that was really impactful to see him losing movement while I was doing movement like six days a week.

I want you to be the stars of the show.

I don't want to be the star of the show.

I became unsatisfied with adaptive dance, of you know, "This is the adaptive class and this is the normal class," and everybody being separated.

And so I thought, "Okay, inclusive is the way I want to go with this, so that we're all in there together and we all have the same goal."

[Music] I am Hava Fisherman.

I'm a dancer with Open Arms.

I never thought I could dance.

When I saw Megan, I wanted to join.

It makes me happy that I'm dancing.

My name is Alice Brown.

I am a Open Arms ambassador, and been dancing with them for four years.

I have OCD, which stands for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder.

I got severely bullied at my junior high school and Open Arms has been there for me a lot.

And it makes me so happy, and I don't know what I could do without Open Arms.

...in a totally new space that's different from everybody else's space.

...and sideways ...and curling in, in, in, in, in.

[Music] Just this weekend, a friend asked me, "So how was the pandemic for you?"

And I said, "Oh, it was fabulous."

You know, where, how often do you hear that?

Because the creativity was magnificent of all of the dancers.

I'll be part of Open Arms as long as somebody can get me there.

You have to actually be "Upstanders" on stage, and take care of each other.

Come forward.

Come forward.

And you're going to surround this group.

Upstanders, everybody on your feet!

"You stand up for me, I stand up for you.

We are the Upstanders!"

Freeze!

And then the show is over.

Here we go.

Ssssssss... Hhaaaaa... Voice: What is strength for you?

Megan: How do you know you're strong?

Heather: Because with my disability, I never thought I could dance.

[Music] "We are the Upstanders!

We are the Upstanders!"

"With open arms, we are the Upstanders!"

[Cheering] I thought it went really good.

How about you, Hava, did you have fun?

Yeah.

Yeah.

Everyone performing is a person, and through their joy of dance they have a message.

Thank you for enjoying the show!

So I hope that they take away our message of compassion.

Basically, all bodies are dance bodies and we're all here for one another.

And we're all here to bring joy and compassion to one another.

Idaho Public Television supporters will be very familiar with our next artist.

For years, painter Fred Choate has amazed viewers, as he quickly creates a landscape painting in our studio.

But Choate also spends countless hours on his paintings, and derives great strength from his art.

I want to portray the sacred of the landscape.

I'm a fourth generation Idaho native, and I've just really bonded and relate to the land here.

It was the mid 90█s I met a an artist named Tom Szewc, and he taught me a method, a very traditional 19th century method of painting, and it just made sense to me.

It just made total sense.

I block in all my colors first, and I do that in order to get a sense of depth in the canvas.

When you start with the darks, it's like a key in music.

You establish a base there and then you can play off of that all through the painting.

Tom wanted me to go meet a painter in eastern Idaho.

So we went over and took a workshop from him.

And about halfway through the workshop we were at a Chinese restaurant and I explained to Tom that I'm glad I came.

I can see what it takes to make it, and I don't have what it takes.

You know, I'll paint for a hobby, but I█m through chasing the dream.

And I got a fortune cookie, I've got it framed up here on the wall behind me in the studio, and the fortune cookie says; Art is your fate: Don't debate.

And the next morning we went up to Mesa Falls, and I did this wonderful little painting of Mesa Falls, which I still have.

And I've been even more serious after that.

I would say post-COVID, my paintings take a little longer.

Because I've started putting figures in more of my paintings.

I had three months of cancer radiation treatments that ended the day the governor shut the state down.

So that period really put me a lot more in touch with my mortality.

In isolation, I all of a sudden had, I became the monk out here in my studio and my paintings became much more sacred.

And then that's when it occurred to me to start taking a little more time to tell a story instead of just doing a very quick impression.

Now, it was more time to make a few more complete sentences.

Just a minute.

Just a minute, Danica.

My little black and white dog had recently died.

And I was working on a painting, a big painting, a big panorama of the Sawtooths.

And I put a little tiny guy with his little black and white dog walking beside him.

And I, and I called the painting Sawtooth Soulmates.

And it's one I sold.

I had, you know, that's what I do, I sell paintings, but this is one I kind of wish I hadn't sold.

Art and the desire to produce art has been a part of me all my life.

Now it's who I am before I█m me.

It's, you know, I breathe, I eat and I paint.

It's that much a part of my core now.

We hope you've enjoyed this edition of “createid.” If you'd like to watch any of these pieces again, you'll find them all on our website.

And for even more stories, check out our YouTube channel.

You can also follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

Just search for “createidahoptv.” For “createid,” I’m Marcia Franklin.

Thanks for spending time with us.

And now, go create!

Major funding for “createid” is provided by the Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S1 Ep9 | 3m | Artist Nick Reddick sees value in things where other people can’t. (3m)

Clip: S1 Ep9 | 2m | See some of the works in "Timescape(s)" exhibition for emerging Pacific Northwest artists. (2m)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

createid is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding provided by the Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.