Decoding COVID-19

Season 47 Episode 10 | 53m 38sVideo has Closed Captions

Scientists race to understand and defeat the coronavirus behind the COVID-19 pandemic.

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has upended life as we know it in a matter of months. But at the same time, an unprecedented global effort to understand and contain the virus—and find a treatment for the disease it causes—is underway. Join doctors on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19 as they strategize to stop the spread, and meet the researchers racing to develop treatments and vaccines.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Carlisle Companies and Viking Cruises. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust and PBS viewers.

Decoding COVID-19

Season 47 Episode 10 | 53m 38sVideo has Closed Captions

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has upended life as we know it in a matter of months. But at the same time, an unprecedented global effort to understand and contain the virus—and find a treatment for the disease it causes—is underway. Join doctors on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19 as they strategize to stop the spread, and meet the researchers racing to develop treatments and vaccines.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch NOVA

NOVA is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

NOVA Labs

NOVA Labs is a free digital platform that engages teens and lifelong learners in games and interactives that foster authentic scientific exploration. Participants take part in real-world investigations by visualizing, analyzing, and playing with the same data that scientists use.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ (thermometer beeps) ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: A world turned upside down... KIZZMEKIA CORBETT: We are in a dire situation.

(ventilator hisses) NARRATOR: ...with deserted streets and hospitals filled to the breaking point.

MATTHEW LEBOW: Everyone is at their limit.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Chaos caused by the tiniest of enemies, thousands of times smaller than a grain of sand.

GALIT ALTER: We've seen pathogens emerge all over the world.

We just don't really know what we're dealing with.

(sneezes) ALICE BEAL: This is much more contagious.

And it's changed how we practice medicine.

DAN BAROUCH: If the majority of the population gets infected, there will be enormous loss of life.

NARRATOR: How can we stop this invisible killer that is baffling scientists?

♪ ♪ NAHID BHADELIA: There are people who get this infection shedding the virus before they get sick, and may never have any symptoms.

NARRATOR: A global race to find treatments for the sick and a vaccine to protect the healthy.

BHADELIA: This ends with most or all of us being immune to this virus, and ideally, that's through a vaccine.

NARRATOR: Can solutions that usually take years... BAROUCH: We are trying to move as fast as we possibly can.

NARRATOR: ...be found in a matter of months?

CORBETT: It is an extremely revolutionary approach.

To get into a phase-one clinical trial 66 days after the sequence of a virus is released is a world record.

NARRATOR: Will we face more waves of infection before science can defeat the coronavirus?

DAVID PRIDE: Time is the one thing we don't have right now.

NARRATOR: "Decoding COVID-19"-- right now on "NOVA."

♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: Major funding for "NOVA" is provided by the following: ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Wuhan, China.

December 31, 2019.

Reports of an outbreak of a mysterious illness.

(horn beeps) Symptoms include a fever, a dry cough, and in some cases, severely compromised breathing.

♪ ♪ The international press picks up the story.

Scientists in China are trying to determine if a new virus strain is responsible for a pneumonia outbreak in the city of Wuhan.

NARRATOR: For the moment, it seems a world away.

As of now, there has not been a U.S. infection, as of yet.

NARRATOR: But for some scientists, this is exactly the early warning signal they've long been dreading.

REPORTER: The future of the people of China, and not only of Asia, but of the world, could be at stake here.

♪ ♪ BHADELIA: I think all of us held our breath.

Because the question was, could this be that combination of a virus that's both easy to transmit and perhaps maybe not as deadly as what we might see with Ebola, but still have just devastating impact on the resilience of our communities?

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The initial fear is that some kind of virus might have jumped from an animal to a human and then spread.

It's happened before.

♪ ♪ One possible way transmission can occur is in markets where domesticated and wild animals are kept in close proximity, common throughout Asia.

MICHAEL OSTERHOLM: And you can see hundreds and hundreds of different animals of every imaginable creation... (people speaking in local language) ...from many different locations that are sold as food.

NARRATOR: Wet markets were a major suspect in the deadly SARS outbreak that began in 2002.

It spread to nearly 30 countries, infected over 8,000 people, and killed 774 before it was contained.

But some scientists believed the world had actually dodged a bullet.

(crowd cheering) That a future epidemic could be much, much worse.

And in January, there are signs that that future may have arrived.

Because this virus appears to be more contagious and stealthier.

♪ ♪ As alarm over the virus grows, researchers scramble to analyze it.

Then, on January 10, a major breakthrough: Chinese scientists publish the entire genome of the mysterious pathogen.

♪ ♪ Rhiju Das, and scientists worldwide, begin to decipher a genetic sequence that's never been seen before.

The virus actually has probably been out there in the world and evolving for, probably for a while.

Probably in bats, actually, and then maybe through an intermediate animal that we don't yet really know, it's now jumped into humans.

So it's not a novel entity on Earth, but it is novel in humans.

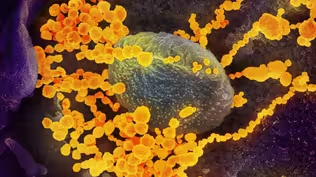

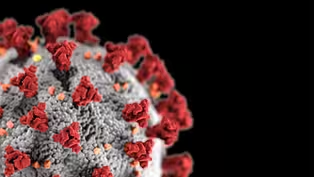

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: It may be novel to us, but it belongs to a family of pathogens called coronaviruses, named for the spikes that protrude from their surfaces, giving them a crown-like appearance.

Coronaviruses are little more than a set of genetic instructions wrapped in a fatty shell with protein spikes.

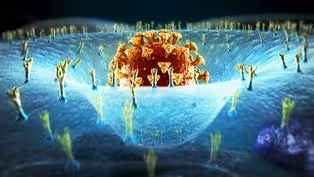

These spikes are like keys, which lock into receptors on cells in your lungs and elsewhere.

Once the virus enters, its cargo of genetic code takes over the cell's machinery and makes new viruses, which head off to infect more cells.

At the National Institutes of Health, immunologist Kizzmekia Corbett studies these pathogens.

CORBETT: Coronaviruses, there are hundreds.

We've heard about MERS and we've heard about SARS.

There are four additional viruses that circulate in humans and cause some level of cold and sniffles and throat aches in people every single year.

NARRATOR: Scientists estimate there are more viruses in the world than stars in the universe.

Luckily, most are harmless, whether they're around us or in us.

And many have left their mark in our DNA.

DAS: When the human genome was sequenced at the end of the last century, I think one of the big surprises was that our genomes are full of the fragments of viruses.

And they're basically the remnants of all of these relatively harmless viral infections that we're constantly undergoing.

NARRATOR: The danger can come when we run into a virus we've never met.

♪ ♪ DAS: When a virus jumps from another animal and finds a way to infect a human, they typically have not evolved to be a nice partner to us.

They will replicate like crazy.

PRIDE: It's very difficult on a cell to be infected with the virus, because the virus sort of says, "Stop doing what you're programmed to do.

Instead, do what I program you to do."

DAS: Our human bodies haven't had enough time to evolve defenses to make sure everything's under control.

And those are the viruses we have to worry about.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In China, word of the virus is traveling.

(speaking Chinese) (translated): I heard about an unknown pneumonia spreading in Wuhan in early January.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Liu Qi is a 21-year-old university student in Wuhan.

The news had been saying it's not a big deal.

I went on with my life.

NARRATOR: But then, on January 17, Liu comes down with what he thinks is just a seasonal bug.

QI (translated): I thought it was a regular cold.

NARRATOR: Four days later, he develops a fever.

I called my dad, told him my symptoms.

He thought it was weird and asked me to return home A.S.A.P.

We went to the hospital for a check-up that night.

A scan showed my lungs were infected.

NARRATOR: The doctor gives him a prescription and tells him to stay at home and rest.

Until then, he hasn't been terribly anxious, but that changes.

(Qi speaking Chinese) (translated): As soon as I started taking the medication, my symptoms got worse.

I lost my appetite, I couldn't keep anything down, and I had terrible diarrhea.

I felt really bad.

NARRATOR: Liu's fever is a sign that his body is under siege from a foreign invader and starting to fight back with its only available weapon: his immune system.

DAS: It's like a thriller.

There are bad guys and then there are good guys, okay?

And the bad guys are viruses and bacteria and foreign junk that is always coming, intruding in our body.

NARRATOR: The "good guys" are billions of immune cells and proteins that are constantly on the lookout.

CORBETT: They will essentially act like a police force, where they see the invader, this virus that's coming to set up shop, essentially, in your lungs, in your nose, in your throat.

♪ ♪ ALTER: The immune system begins to sense that there is a foreign invader inside the body.

DAS: They go back to headquarters, which is in our lymph nodes, and they say, "We got to go and figure out a response."

ALTER: And what those cells do is, they can start to educate the immune system of what exactly this pathogen looks like.

NARRATOR: While this battle rages, Liu's symptoms worsen.

I start to worry that I caught the disease.

I never felt so much pain.

I felt like I was dying.

I was scared.

NARRATOR: A second scan reveals an infection from the COVID-19 virus is spreading throughout his lungs.

Meanwhile, it's spreading throughout the world, as well.

♪ ♪ After surfacing in Wuhan, the virus rapidly crosses borders, reaching Thailand, Japan, South Korea... and beyond.

JEFFREY SHAMAN: When we saw this outbreak, we were struck by the rapidity with which it spread geographically within China and how it quickly translocated to other countries around the world.

NARRATOR: Hotspots soon erupt in the Middle East and Europe, with Italy hit hardest.

ALTER: It was really like tracking a race.

And so what that told us is that even before symptoms began to manifest, that's when individuals could be highly contagious.

NARRATOR: Within months, the virus reaches every continent except Antarctica, including North America.

SHAMAN: There are a lot of people who are unaware that they're infected.

They never become symptomatic, or if they do, they're mildly symptomatic.

They don't stay home.

They ride public transportation, they go to work, they get on airplanes to take business trips.

They take the virus to new places and introduce it to new communities, where it then spreads further.

Coronavirus cases in the tri-state continue to rise.

This morning, there are 44 confirmed cases of the disease... (birds squawking) ♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In late February, the virus still seems like a distant threat to many New Yorkers, like Jessica Brown, who lives in Queens with her husband, three children, and her father, George.

♪ ♪ At age 73, keeping up with his three active grandchildren is not a problem.

MATTHEW LEBOW: My grandfather's personality was "one of the kids."

He was the first one to come up with doing something goofy or silly.

He was at every sporting event.

He was at every graduation, every spelling bee, every birthday.

BROWN: Dad never knew what the adventure was going to be.

But he never said no.

He always just said, "There I am, kidnapped again."

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The first week of March, George makes it to four of his granddaughter's basketball games and a Broadway play, unaware that the coronavirus is all around him and could be contracted with astonishing ease.

Studies reveal it can remain infectious on some surfaces for up to three days, or suspended in the air for a short time after an infected person coughs or breathes.

LEBOW: When my grandfather first started to get sick, it was, you know, "I have a stuffy nose, but, you know, I'm okay, I'm hanging in there."

We all just took it as if it was a common cold.

NARRATOR: Over the next three days, his symptoms rapidly get worse.

BROWN: I said, "Dad, I think you have to go to a doctor.

I just don't like the way you look."

And he said, "Oh, stop it, stop it.

Let's see what happens when you get home from work."

Friday, I get home from work, he was shaking.

My mom called me the next day and that's when she said, you know, "Pops isn't looking good."

You know, "He's starting to tremble "and he just seems like he's moving significantly slower than he was the day before."

BROWN: So I brought him into the hospital.

They didn't think that it was coronavirus, but they did take him and put him in isolation anyway, 'cause this was just the beginning of it.

They gave my husband and myself a mask and asked us to please wait in the waiting room.

I saw him leave to go get a chest X-ray.

I said, "How do you feel?"

He looked better.

They gave him some oxygen.

He gave me a thumbs-up, and told me to bring him some newspapers.

NARRATOR: Hours later, George is taken to the I.C.U.

and diagnosed with COVID-19.

The liaison between the critical care team and his family is veteran palliative care doctor Alice Beal.

BEAL: This is somewhat reminiscent of the AIDS crisis, in the fear that people have.

But this is much more contagious than AIDS ever was.

And it's changed how we practice medicine.

We touch, we examine, we listen.

In this pandemic, I don't even get to see my patients.

I don't even get to talk to many of them.

NARRATOR: That is certainly true for George, who, like many coronavirus patients, is struggling to breathe.

♪ ♪ In healthy lungs, tiny air sacs deliver oxygen to blood vessels.

But as the virus kills cells, and the immune system fights back, inflammation results, filling the lungs with fluid and debris, blocking the flow of oxygen.

ALTER: What happens to some of these individuals that go down this severe path is, they begin to make this massive burst of inflammatory molecules that we call the cytokine storm.

Now, once that signal or that alarm goes off in the body, all kinds of other immune cells that we have in our system start to swarm in.

That then basically sends the immune system into this incredible disarray.

BHADELIA: Your own immune system then becomes an enemy to your body.

So in that combination of both the direct damage that the virus does and the inflammation that comes from the immune system overreacting to the virus, you get a scenario where people start to have trouble breathing.

NARRATOR: Many patients, like George, end up needing a mechanical ventilator to do their breathing for them.

(voice trembling): Throughout the night, he started showing symptoms, and they had to put him on a vent.

And once they said that they put him on a vent, I just knew that it wasn't good.

It was such a shock to his daughter that when I called her, she just couldn't understand how this could happen.

I told her this is what this disease does.

BROWN: She said that many things are going on in Dad's body right now.

His enzymes are low, and it's showing that he may be having a massive heart attack.

She wanted to come in.

She desperately wanted to come in.

She said, "I won't even bring my kids, just me."

And I said, "No, it's just too unsafe."

No families are allowed in the hospitals at all, anywhere.

BROWN: 15 minutes later, I called her back, and I said, "Please, we need closure."

And she said, "You hold on, you give me ten minutes "and gather up your troops, and we are going to figure something out."

BEAL: There are no phones in the rooms in the I.C.U.

and he didn't have a smartphone.

One of my residents figured out we could hook the intercom up to a speaker phone.

It wouldn't be private, but the family could say goodbye.

LEBOW: My whole family was together in our kitchen, and, and our dog Charlie, and she had us go on speaker phone over an intercom into my grandfather's room.

(voice breaking): And all five of us were able to say our goodbyes to my dad.

Obviously through a lot of tears and crying.

And that was the closure that we needed.

He heard us, he heard us say goodbye.

LEBOW: Seeing these people going to the hospital alone and not being able to bring their loved ones and have no one there, I think that everyone hearing it-- for the healthcare professionals and for the patients there-- that it would give a sense of hope.

And yes, you're in the hospital, you're alone, but the entire world is thinking about you and praying for you to pull through and, you know, get through this.

(machinery beeping) (siren blaring) NARRATOR: After his grandfather's death, Matthew is called back to work.

As a New York City E.M.T., he is desperately needed.

LEBOW: When I went back to work, it seems that we were smack in the middle of chaos.

And I could look at my partners' faces and just see that they're already drained.

And they would just shake their heads and say, "Matt, it's bad."

(machinery beeping, people talking in background) We're bringing people to the hospital and we're waiting three-and-a-half hours to get them into a bed in the hospital because there's nowhere to put them.

So, they're just sitting in our stretchers declining.

NARRATOR: 16-hour shifts, answering call after call, are now the norm, as is telling patients' families that nothing can be done.

Just shocked at how many are...

I'm actually seeing deaths.

We just came out of one pronounced.

LEBOW: We're coming across these patients who have been tested for the virus, and they tested positive, and they're sent home.

We're getting called into people's homes, and they're in cardiac arrest.

And they're not breathing, they have no pulse.

And, you know, we're asking what happened, as we begin doing CPR.

It's almost too late.

We can't help anybody.

Everyone is at their limit.

And all we can think about is when it's going to end.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Across the city, Jeffrey Shaman is asking the same question.

Using data collected by the "New York Times" and the U.S. Census Bureau, he models how the outbreak might evolve under different control measures.

In one scenario, if the virus is allowed to spread freely, infection rates would soar, overwhelming the healthcare system.

SHAMAN: We get a trajectory that shows a very aggressive outbreak, where roughly 75% or greater of the population is ultimately infected by this virus by the end of the summer.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: And if regions adopt only partial control measures, the results would hardly be better.

Only strict social distancing imposed nationwide would slow the rate of infection.

LEBOW: The spread of this virus is no joke, and it is crucial for people to stay home.

Speaking about how the virus spreads and how people could be carrying it and infecting others without even knowing it really touches close to home for me.

(voice trembling): Because I was sick before my grandfather.

And how do I know that that wasn't the virus in me?

And I was hanging out with him while I was sick.

We went for walks, we went to get coffee.

(crying): And what if I'm a carrier and I gave it to him?

NARRATOR: But strict social distancing comes with its own tremendous toll-- economic paralysis, mass unemployment.

SHAMAN: And that's the thing that makes people really anxious.

And I totally get that, because on one hand, we don't want people to die here.

On the other side, unemployment rates are skyrocketing.

People don't necessarily have food security.

And the economic consequences of doing this over maybe even a year or longer could be utterly devastating and hard to pull out of.

OSTERHOLM: There are 320 million Americans today.

We have every reason to believe that over the next 16 to 18 months, at least half of them will become infected.

So, 160 million people.

This virus will find people who are susceptible.

Therefore, as soon as we have the least bit of let-up for any kind of these intensive control measures, the virus is going to come back.

(people talking in background) NARRATOR: So is there a way to safely restart our economy?

Perhaps, if we embrace strategies that stop transmission-- isolating the infected, instead of shutting down an entire country.

BHADELIA: It's case-finding, it's finding people who are sick, and it's contact-tracing-- looking at everybody else the person who is sick has been in contact with.

Then bringing everybody who we know is sick to care so they do not continue to transmit that infection in the community.

MEDICAL WORKER: Can you pump your hand a little bit?

NARRATOR: But is there another possible solution... All right, a little pin prick.

NARRATOR: ...using blood tests to determine who may already have immunity?

Oh, you're good.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: To find out, Duane Wesemann is biking samples of blood plasma across Boston, to the lab of Galit Alter.

Hey.

Hey, Galit.

Hey, Duane, thanks for bringing them over.

How many do you have today?

Okay, we have about 40.

Okay, that's a good batch, thanks.

NARRATOR: Alter is testing the plasma for antibodies-- proteins in the immune system that find and destroy invaders.

ALTER: Antibodies are molecules that can see the target absolutely specifically.

And those antibodies start to stick to the pathogen and to the infected cells and start to direct the immune system to kill those particular targets as rapidly as possible.

And so these antibodies constantly mutate and they constantly evolve in order to bind tighter and more specifically to the virus.

How's it going over here?

NARRATOR: For Alter's test to be effective, it has to be able to tell the difference between antibodies to the COVID-19 virus and other coronaviruses, like those that cause some common colds.

ALTER: So this is the common cold, and this is the novel coronavirus.

STEPHANIE FISCHINGER: This looks good.

We just don't want any, like, false positive detections.

NARRATOR: A single plate contains the plasma samples from 175 patients.

ALTER: So what our tests do is, they essentially allow us to detect exactly how much antibody is there through particular reagents that change colors.

NARRATOR: If COVID-19 antibodies are present, coloring agents will turn the plasma blue, and then yellow.

Everything that's yellow will be positive, and of course, there's different levels of positivity.

ALTER: Depending on the intensity of the color that appears inside the well, we can actually tell the exact amount of antibody you have in your immune system.

And it gives each well a number.

The higher the number, the more antibodies this person had.

Most commercial tests are only giving us a yes or no answer, you do or don't have antibodies.

What our particular antibody test does is, it tells us exactly the level of antibody you have in your blood, Because we believe that this level is really what is going to dictate whether or not you are going to be protected from infection or not.

NARRATOR: Even if you have the right level of antibodies, are they the right type to neutralize the virus?

If so, how long will they protect you?

Are they like measles antibodies, which may confer lifelong immunity?

Or seasonal flu antibodies that shield for less than a year?

ALTER: Can you put the last guy here?

Where's the last guy?

NARRATOR: To find out, Alter's lab is working with Boston hospitals to follow patients with COVID-19 antibodies for the next two years.

The people who are testing positive do have very high levels of antibodies.

NARRATOR: She will check their antibody levels periodically and keep track of who gets reinfected.

There is this idea that if you have a positive antibody test that this may be sufficient for you to return to work and reenter society.

But what we've learned from many pathogens over the years is that it's not black and white.

And what this type of analysis allows us to do now for the first time is to define the specific characteristics of an antibody and the absolute level of antibody that gives you complete protection from disease.

Once we have that number, we have the ability to give out those passports that will allow people to reenter the population safely.

NARRATOR: While scientists work around the clock to find ways to understand the link between antibodies and immunity, some doctors resort to an old practice-- borrowing immunity from recovered patients.

ALTER: One of the oldest therapies that we have in medical practices is the transfer of immune plasma to people who are sick.

And that's really what opened up this entire field of antibody therapy.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In Wuhan, after a torturous three weeks, Liu has tested negative for the virus.

Today, he's making another trip to the hospital.

But not because he's sick.

Doctors hope that Liu, as well as other recovered patients, have immunity.

The antibodies that his body manufactured to fight the virus are still coursing through his blood.

The virus is still a threat to others, so Liu offers to donate blood plasma.

But it's not easy.

Drivers are wary of being exposed.

Liu does his best to be reassuring.

(Qi speaking Chinese) (translated): I saw so much tragedy during this pandemic.

My motivation is to help doctors, help them save more people.

I wish I could have been a doctor.

So, as a normal person, I feel that donating blood is what I can do now.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Inside, staff wear ample protective gear.

He's checked for fever, examined, and asked about his general health.

NURSE: QI: QI (translated): During the donation, your blood flows into a machine that separates the plasma from red blood cells and platelets.

Those come back into your body while the hospital keeps the plasma, which has antibodies in it.

NARRATOR: As he leaves, staff give him a can of protein powder to help keep up his strength, along with thanks and a certificate marking his contribution.

Plasma like Liu's is being used as an experimental therapy for severely ill patients.

At this point, doctors are desperate for treatments that will help.

BHADELIA: Emerging infectious diseases are challenging because we're learning about both the virus and the disease as we're responding to it.

New evidence is coming out about how this virus is transmitted, where the virus lives in the human body.

And so we are at a place where we're making medical decisions on the go as science changes.

NARRATOR: With reports of COVID-19 ravaging hearts, livers, and kidneys, and causing blood clots and strokes, the health risks seem worse than ever.

Although severe illness is less common for people under 65, no one can know for sure how the virus might impact them.

BHADELIA: We're seeing patients of every age walk through the door.

It is a misnomer to say that the young are immune to this.

We constantly see people who are in their 20s, 30s, 40s, you know, and some who do not have any medical conditions, because it's a brand-new virus, and none of us are immune to it.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Since no one is immune, could there be a treatment to reduce the severity of the disease?

That is something Robert Davey at Boston University is racing to find out.

DAVEY: Our ultimate goal is to have the designer molecule which will specifically attack the virus and do nothing to the rest of your body.

Something that stops the virus dead in its tracks and doesn't affect you in any way whatsoever.

NARRATOR: This is a level-four biosafety lab-- one of only a few in the U.S. DAVEY: Biosafety level four is when you're in a bubble, a suit that looks like what the Michelin man has on.

♪ ♪ It's inflated by air.

So this is the highest level of protection.

RONALD CORLEY: This is probably the safest place in the country to be right now.

Any laboratory facility that studies emerging pathogens is designed around safety and security.

(lock clicks) NARRATOR: The CDC does not require this level of safety for the coronavirus.

But it was much more efficient for this lab to launch research at level four, because before COVID-19, Davey was studying Ebola.

Now he's testing thousands of drug compounds that just might be the right shape to disable this novel coronavirus.

This is what the process looks like.

DAVEY: So we have the plates with the 384 little wells in them and each one gets cells and drug.

And then we take those plates to the containment lab and we add virus to all the wells.

NARRATOR: The concoction of human cells, virus, and potential drug is then set aside to see if the virus will infect the cells or if the drug will stop it.

Next, Davey analyzes the results.

DAVEY: We put on a dye onto the cell so it's colored.

And every time a cell is infected, that cell will now glow green.

And you just add them up-- just count up the dots.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Here, cells glow blue.

But if they become infected, they glow green.

The fewer green cells, the more effective the drug.

DAVEY: And that's how you know if the drug is working.

♪ ♪ I know people who are extremely anxious about the pandemic.

And I also feel that anxiety.

I have two daughters that work in supermarkets.

I worry about them every day.

And I have elderly parents and I want to make sure they're still here after this.

I'm trying to as quickly as possible get to a treatment, but I've got to be safe and I've got to be careful and I've got to do scientific rigor.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: In late April, the N.I.H.

announces that preliminary data from a study of the antiviral drug remdesivir suggests it helps severely ill patients recover a few days sooner.

Although the results are promising, many believe antiviral drugs alone won't be enough to save us from the ravages of COVID-19.

LEBOW: For myself and everyone else on the front lines, we fear every day for our loved ones.

People that I work with are sleeping in their cars because they're scared to go home to their families.

We're really not going food shopping because we're worried about giving it to other people.

Thank God for the people that are donating food to where I work.

BEAL: The health care workers are under a lot of pressure.

They're exhausted, but they're also retraining to be in a marathon, so that we can continue this for a long time.

BHADELIA: So how does this end?

This ends with most or all of us being immune to this virus, and ideally, that's through a vaccine.

It cannot be through all of us getting sick at the same time.

PRIDE: If you just sort of let it run wild in your population, sure, you'll eventually get to that immunity that you'd like, but it might take, unfortunately, a million deaths for you to be able to achieve that.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: The Holy Grail for science is now a vaccine.

♪ ♪ In January, once the coronavirus genome was published, scientists around the world sprang into action.

CORBETT: I set alerts on all of my mobile devices and my computer.

NARRATOR: N.I.H.

immunologist Kizzmekia Corbett is one of an elite army of scientists trying to find the perfect formula for that lifesaving vaccine.

CORBETT: It was a Saturday morning, and now you have what are considered to be ants in your pants around getting your experiments started.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: All vaccines have the same goal, whether they're made from weakened or dead pathogens or pieces of them.

DAS: Vaccines work by giving our bodies, and specifically our immune systems, a preview of what an invading virus would look like.

NARRATOR: The idea is to trick the body into thinking it's being infected.

CORBETT: Typically and historically what has been done is, by giving the body just a weakened form of the virus, so that the body makes an immune response, but the person doesn't get sick.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: But creating weakened viruses, like the one used in the measles vaccine, can take years.

To speed things up, dozens of labs are betting on revolutionary new approaches to vaccines, building them with genetic instructions, sometimes in the form of RNA.

CORBETT: RNA is used by cells day in and day out.

The purpose of RNA is to tell the body what types of proteins to make.

NARRATOR: In this case, an RNA vaccine would tell the body to make the coronavirus spike protein.

CORBETT: At the end of the day, you're really just calling up the cell and saying, "Hey, cell, can you make this protein so my body can make an immune response to it?"

NARRATOR: The hope is that our immune cells would identify the spike as a foreign threat and trigger the production of antibodies, as well as memory cells.

CORBETT: They'll remember that spike protein well enough, and in so much detail, that when your body sees that spike protein again, those memory cells can trigger the body to respond in a very specific and quick manner so that you don't get infected.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Many researchers-- including Corbett and Rhiju Das-- are focusing on RNA for one critical reason.

The advantage of RNA vaccines is that they're super-fast to make, which is absolutely critical in the current pandemic situation.

NARRATOR: Though this approach is fast, no one knows if it will actually work.

DAS: There are not yet FDA-approved RNA vaccines that have gone on the market.

It's still not clear whether these RNA molecules will be safe to inject into everybody.

NARRATOR: In the past, there have been a few experimental vaccines which made infections worse.

That's why clinical trials are so important.

In March, just over two months after the coronavirus genome was released, volunteers in Washington state started receiving the experimental RNA vaccine Kizzmekia Corbett helped design.

CORBETT: To get into a phase-one clinical trial 66 days after the sequence of a virus is released is, you know, a world record; it is incredible.

NARRATOR: But even if an RNA vaccine passes clinical trials in record time, there will still be other major hurdles, including shelf life.

DAS: The current RNA vaccines are stable if they're freeze-dried or kept under ultra-cold temperatures.

NARRATOR: But at room temperature, or even in a standard refrigerated shipping container... DAS: These RNA vaccines, they're gonna decay.

They seem to lose their potency as vaccines on a timescale of days.

Their expiration date is so short that they wouldn't be active in the time it takes to ship them from, say, Newark, New Jersey, to California, and down to the clinic for me to get the shot.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: That's a problem when the goal is to manufacture and deliver coronavirus vaccines to billions of people across the planet.

To find a solution, Das's team is trying to custom-design the RNA molecules so they'll fold into more stable shapes.

DAS: What we're doing here is, we are designing these RNA vaccines to fold into little tiny packets.

But we don't know exactly what the right shape is.

NARRATOR: To find the right shape, Das is recruiting help from an unlikely crew-- online gamers.

DAS: We're trying to recruit potentially millions of people to come play a video game.

NARRATOR: Some players' solutions to molecular puzzles are tested in Das's lab with real RNA.

DAS: And the solutions that they're providing very well could become a medicine that then is injected into billions of people.

NARRATOR: RNA isn't the only new contender in the vaccine race.

Through here is... NARRATOR: Dan Barouch's lab has spent years developing DNA vaccines against H.I.V.

Now his team is applying a similar approach to the coronavirus-- creating a DNA vaccine that codes for the spike protein and relies on a common but powerful helper.

BAROUCH: We inserted the coronavirus spike protein DNA into a common cold virus.

Common cold viruses are very good at getting into cells.

So we essentially hijack that property of the common cold virus and utilize it to help get the coronavirus spike protein gene into human cells.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Barouch hopes that clinical trials of this vaccine will start in September.

ALTER: There are over three dozen different vaccines that are moving into preclinical and clinical testing already.

The pace is really inspiring.

We have never seen this for any other pathogen to date, where so many different vaccine developers are really ready to go to come up with a solution to this particular infectious disease.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Hopes are high that one or more of these vaccines will work and help end the pandemic.

But testing and manufacturing vaccines can take years, and there are no guarantees.

Without a vaccine, the main tool we have is our behavior.

♪ ♪ In Wuhan, an unprecedented reopening experiment officially begins on April 8.

Residents are allowed to travel and move about.

(Qi speaking Chinese) (translated): Every time I went downstairs to shop for food, I noticed there were more and more people outside.

That was a very good sign.

NARRATOR: But it's hardly back to normal.

Fear of a second outbreak runs high, and many restrictions remain in place.

Anyone entering or leaving a building or public space is required to use their phone to scan special location-marking codes.

(Qi speaking Chinese) The gate of your complex is the first checkpoint you need to go through when you try to go out.

Using apps like WeChat or Alipay, you scan the QR code and tell the app if you are entering or exiting.

The system records your location automatically.

Based on your current health condition, you're given a code.

Anyone with a green code is allowed to leave freely, but if you have a yellow or red code, which means you've had contact with someone infected-- or you're infected-- you can't go anywhere.

NARRATOR: At the same time, monitors take body temperatures at each access point.

These measures have been introduced to squash new outbreaks.

They track each person's movements in order to alert them later if it turns out they were exposed to the virus.

If someone who was in the same place at the same time as you is diagnosed later, you'll get a notice immediately.

Then your status becomes yellow, and you have to isolate yourself at home for a while.

NARRATOR: In that instance, the person notified is flagged, and if they try to scan into a public place during the next seven days, they will be denied entry.

QI: It's all very strict now, but it's for our safety.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: And after being very sick, scared, and locked down for weeks, Liu is relieved to be out and about, no matter what the restrictions, just grateful to be healthy.

♪ ♪ I want to say one more thing.

This outbreak really taught me something.

People are precious.

(in English): Cherish everything you have, be kind to everyone you met.

♪ ♪ NARRATOR: Months after the initial outbreak, the true origin of the virus is still unknown.

Wuhan has dramatically reduced the rate of infection, though the virus still remains.

REPORTER: Today in Wuhan, China, the city at the epicenter of the coronavirus crisis, it's reporting its first new case in more than a month.

NARRATOR: So far, China's approach appears to be slowing the spread.

(people talking in background) Back in the U.S., as COVID infections continue to rise, pressure mounts to reopen the economy.

But are we willing to go as far as China to prevent new waves of infection, which some experts say are inevitable?

♪ ♪ Or will data collection to track the virus face a backlash over privacy concerns?

We have never seen a Silicon Valley product launch quite like the one on Friday.

NARRATOR: In response, Google and Apple have developed new software that anonymously tracks COVID exposures.

They are teaming up to create voluntary coronavirus tracing and tracking software.

(tone pings) NARRATOR: It allows a user's phone to broadcast changing codes to phones nearby.

If a person is later diagnosed with COVID-19, everyone using the software who was in close proximity in the previous two weeks is notified that they've been exposed.

No one's identity is revealed.

It's a voluntary program that could slow the spread.

But many experts agree this tiny virus remains an enormous threat.

So, until we have effective treatments and vaccines, how do we stay safe?

♪ ♪ BHADELIA: Lifting the lockdown is not the end.

It doesn't mean we go back to normal.

It means that our lives are altered, at least in the medium term, and potentially forever.

OSTERHOLM: What we have to figure out is, how do we get back into not being in total lockdown, but at the same time, minimizing the impact that this virus might have?

But it's not going to be easy.

Hello!

Hello!

♪ Happy birthday to you ♪ ♪ Happy birthday to you ♪ BHADELIA: One of the hardest parts of this disease is how we are so separated from each other.

♪ Happy birthday to you ♪ (cheering and applauding) BHADELIA: And I think it underscores for me the importance that it's not social distancing-- it's physical distancing and social cohesion.

We still have to connect with each other.

And pandemics like COVID-19 tell us how interdependent we are on each other.

Truly, an outbreak anywhere is an outbreak everywhere, because we are connected.

Every part of the world is about two flights away.

(airplane engine roars) DAS: The pandemic has crystalized a sense of purpose for us.

We're at a point where really every day counts.

It's a horrible situation to be in, but the technologies that we can develop against the coronavirus, we'll be able to deploy it hopefully to prevent any future pandemic.

(sirens wailing) OSTERHOLM: And it's our legacy.

It's not just how we get through the pandemic, but what we do about it afterwards.

We can't let this happen again.

And to me, this is like a moonshot.

Imagine one day, if we could take away the threat of these kinds of pandemics from happening again.

That would be a gift to our, our kids and grandkids, second to none.

♪ ♪ ANNOUNCER: Major funding for "NOVA" is provided by the following: ♪ ♪ This program is available with PBS Passport and on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S47 Ep10 | 26s | Scientists race to understand and defeat the coronavirus behind the COVID-19 pandemic. (26s)

How Viruses Like the Novel Coronavirus Evolve

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep10 | 2m 53s | The virus likely is not a new entity on Earth, but it is new in humans. (2m 53s)

How Wuhan is Using Digital Gatekeeping to Reopen

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep10 | 2m 47s | To reopen the city, Wuhan, China is using digital gatekeeping to contact trace. Here’s how (2m 47s)

When You Lose a Loved One to Coronavirus

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep10 | 6m 36s | Hear George’s family recount his tragic story. (6m 36s)

Why Antibody Tests Don’t Yet Reveal Coronavirus Immunity

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep10 | 5m 59s | Can an antibody blood test tell if you are immune to COVID-19? (5m 59s)

Can Scientists Use RNA to Create a Coronavirus Vaccine?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep10 | 5m 28s | The coronavirus has unleashed global havoc. Learn how scientists are hitting back. (5m 28s)

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep10 | 6m 46s | Learn the science behind the tests. (6m 46s)

What We Know and Don’t Know about the Coronavirus

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S47 Ep10 | 5m 55s | What is covid-19 and should you be worried? (5m 55s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

National Corporate funding for NOVA is provided by Carlisle Companies and Viking Cruises. Major funding for NOVA is provided by the NOVA Science Trust and PBS viewers.