Introduction to "The Nisei Paradox: Justice on Trial"

Clip: Season 8 Episode 1 | 12m 33sVideo has Closed Captions

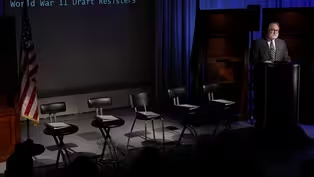

A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII.

In World War II, 44 Japanese American men at Minidoka resisted government conscription into the US military, refusing to be drafted by a country that considered them less than full citizens. Their case is being retold 80 years later by the Friends of Minidoka – and by a group of Idaho lawyers who wrote and produced a play.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer. Additional funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson...

Introduction to "The Nisei Paradox: Justice on Trial"

Clip: Season 8 Episode 1 | 12m 33sVideo has Closed Captions

In World War II, 44 Japanese American men at Minidoka resisted government conscription into the US military, refusing to be drafted by a country that considered them less than full citizens. Their case is being retold 80 years later by the Friends of Minidoka – and by a group of Idaho lawyers who wrote and produced a play.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Idaho Experience

Idaho Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipRonald E. Bush: I'm, I'm going to give you a little backdrop to this play, and this is something I've done at each time it's been performed, because the history is important to the play.

And having a little bit of understanding about, what came before, so to speak, is useful for you to, uh, to see the play and then ponder, what you've seen.

So, as you can probably tell from looking at me, I'm a baby boomer born in 1956.

That was, only a decade after the cataclysmic events of World War two.

And even less time since the war in Korea that ended.

Uh, those wars were still very fresh in the minds of Americans at that time, and in my growing up years.

So I learned about World War II from history classes and books, from listening to my family members, from reading, uh, various accounts by people who had served.

I remember coming across war rationing books in the drawers of my grandparents desks.

I talked with my friends about their own relatives who had been in the war including relatives who had been injured or killed.

Of course, like all of us, I applauded veterans who walked in uniform.

on 4th of July parades.

And I reflected upon the Gold Star Memorial Highway Markers when I travelled.

I learned as well, about the war by reading obituaries of those who had fought in World War II and returned home.

Sometimes having the full extent of their heroism described for the first time in the tributes that are made upon their passing.

I might mention that in regard to the relocation and the people who, were interned in the various camps, that's still something that you see today, in people who were there and passed away and mention is made of that connection.

And that history.

But never in my growing up years.

did I ever learn anything about the government's decision in 1942, following the December 7th, 1941 attack upon Pearl Harbor.

To remove an entire population of people with Japanese ethnic heritage from their homes and businesses along the West Coast, and force them into imprisonment and so-called relocation camps in the interior states.

The elderly, the mothers and fathers, the children, the infants, everyone of Japanese ethnicity first placed under curfew and prohibited from leaving their homes or going any kind of distance away, and then required on short notice to move into so-called assembly centers, necessitating that they abandon or make hasty arrangements to sell their businesses, their homes and belongings.

That huge loss, and take with them only what could be placed in a few suitcases.

And then our government, acting through the War Department, forced these West Coast ethnic Japanese, more than 110,000 in number, most of whom were American citizens, into hastily constructed camps of tar paper shacks, primarily in desolate regions of the interior West, without any regard to constitutional prohibitions against unlawful seizure and unlawful detention, or with any of the protections of fundamental due process.

This was a crisis of war, and the constitutional conscience of our country was left trembling in its wake.

Perhaps understandably, in the moment, but inexplicable in retrospect.

The hysteria and fear germinated by the attack on Pearl Harbor surfaced in the mud of anti-Asian racism that already existed in the country, particularly in the western states.

Almost immediately after the attack, the Federal War Department started to single out and arrest persons of Japanese ethnicity suspected of possible existing or future complicity with the country of Japan.

Who were then set, sent to specific military detention facilities.

Two months after the attack, President Roosevelt signed the infamous Executive Order 9066, implementing his war power to allow the designation of exclusion zones to exclude people from military areas.

The military at that time believed that there was a so-called fifth column of Jap, of ethnic Japanese in the United States, who were planning to spy on, on American military operations and to sabotage the many military bases located on the West Coast.

Under Executive Order 9066.

The War Department then designated the entire West Coast to a point 100 miles inland from the ocean coastlines as a military area.

Then all persons of Japanese ancestry living in the military area were placed under curfew.

Most assets of Japanese nationals were frozen and an exclusion order was issued which required them to move into the assembly centers, where they were detained until moved on to the misleadingly named relocation centers far into the interior.

When the War Department announced that it intended to build one such relocation center in the sagebrush desert of Jerome County, Idaho, Idaho Governor Chase Clark raised hell.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, he had ordered that ethnic Japanese living in Idaho after the attack on Pearl Harbor be confined to their homes until their status had been determined.

He lifted that order after a few days, but instructed law enforcement to keep a close eye on them.

Governor Clark said publicly that it was no secret that there are many men and women in our state today who owe first allegiance to the governments of Germany, Italy and Japan, and that reports of action that aroused suspicions of enemy activity should be promptly made by any citizen to the closest police officer.

When Clark realized that he could not stop the War Department's plans for an Idaho detention center, he took a different tact, saying that no one of Japanese ancestry would be permitted to lease or purchase land in Idaho.

“I can't see us sending Idaho boys out to fight the Japs in the Pacific, and then come back to find Japs in their homes and on their farms.” One Idaho farm grange organization applauded him, saying that its members did not want to see the same Japanese problem that California has had.

Japanese and whites do not mix and co-mingle to the advantage of either race.

Idaho should remain white, and the grange should join with the governor in his fight to maintain it as such.

A Payette, a Payette newspaper echoed the xenophobia, editorializing that the Japanese do not maintain our standard of living, and if they lend anything to a state or community, we are at a loss to know what it is.

Some seemingly lonely voices raised different points of view.

Mr. A. Connell sent a letter to a Boise newspaper stating that Governor Clark was oath bound and honor bound to command the police and powers of the state to preserve constitutional rights to every citizen, irrespective of who their ancestors might have been or what the color of their skin.

U.S.

Senator Worth Clark was asked to convey to the War Department the views of the members of the Twin Falls Chamber of Commerce, who had unanimously resolved that if the Japanese entered Idaho, then, quote, “they should not be allowed to roam loose in the Magic Valley.” Close quote.

Senator Clark, the nephew of Governor Clark, replied to the chamber members that the bulk of the Japanese on the coast are citizens, and we cannot push them around as if they were slaves.

So then, imagine if you will, even though we cannot begin to fathom it unless we had been there, the enormity of what occurred in those years of 1942 to 1945 when the camps closed.

Imagine the foolhardiness and the injustice of forcing more than 110,000 people out of their homes and severing their lives into pieces.

Then crowding them to live behind barbed wire fences and guard towers, and crowded, thin boarded tar paper shacks with little, if any, privacy.

Imagine all of the parts of daily life, schooling, laundry, religion, raising children, cooking, having children, caring for the sick and the aged, trying to create beauty in a place where little beauty existed.

Trying to find a way to replace the self-esteem previously drawn from meaningful work.

All of those parts of our lives that we take for granted, both quotidian and extraordinary, put completely asunder and irretrievable.

So then imagine these things taking place during the war years, the pressures to keep one's head up, so to speak, and keep faith in the country you lived in and were, for most, born in.

Trying to reconcile a sense of duty and patriotism for your country against what had happened to you.

And then imagine that you were a young man when the war broke out, that you were a young man who sought to enlist in the armed services when President Roosevelt described the Day of Infamy at Pearl Harbor and declared war on Japan, only to be refused because your ancestry had labeled you and everyone like you an enemy alien.

And then imagine some months later, when you were asked to enlist because the country needed more soldiers.

But to do so, you were required to prove your loyalty.

In a six page questionnaire asking for detailed information about every imaginable aspect of your life and any possible connection it might have to Japan, that information to be used by the War Department to decide whether you were loyal to the United States.

And finally, imagine that you were a young man who felt that your country had failed you, a United States citizen, along with your family.

A young man whose belief in the promises of the Constitution had been tested by events which had removed you against your will, far from your home and your livelihood, put you in a camp behind armed guard, not free to come and go with no end in sight.

A young man, a United States citizen, whose country refused your efforts to enlist.

Who said you were an enemy alien.

Then presumed you were disloyal to the United States.

And then, after all that sent you a draft notice.

Dozens of young Nisei men in the Minidoka camp received such draft notices and refused to appear for induction.

Hundreds in total across the various internment camps made the same decision.

Those who did so at the Minidoka camp were prosecuted by the United States Attorney, with indictments returned from a grand jury in the Idaho federal court.

Their cases proceeded to trial, in the federal courthouse in Boise.

Chase Clark ran for reelection as governor in the fall of 1942.

He was defeated.

In January of 1943, just prior to the inauguration of his successor, Governor Clark received a phone call from the White House informing him that President Roosevelt had just nominated him to fill the vacancy in the only federal district judgeship in Idaho.

He was concerned, he was confirmed by the U.S. Senate and began his new work as a federal judge in March of 1943.

Judge Clark presided over each of the trials involving the Minidoka Nisei draft resisters.

As he noted at the time, there was no one else to do so.

He was the only federal judge in the district.

This play is the story of those resisters and those trials told in a collective window into those moments in time.

Preview of "The Nisei Paradox: Justice on Trial"

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep1 | 30s | A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII. (30s)

The Nisei Paradox: Japanese American World War II Draft Resisters | Full Performance

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep1 | 59m 3s | A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII. (59m 3s)

Tease to "The Nisei Paradox: Justice on Trial"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep1 | 1m 10s | A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII. (1m 10s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer. Additional funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson...