Nothing But the Truth

Season 5 Episode 2 | 26m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

Two sensational Idaho murder cases 100 years apart, and the power of facts and truth.

In Idaho’s early days, disputes were settled by knives, guns and fists. It took a few zealous advocates to ensure that the rule of law prevailed over vigilantism in the 1800s; and it takes the same dogged commitment to ensure justice in our time. Two sensational Idaho murder cases 100 years apart remind us about the enduring power of truth, justice and fact-finding.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major Funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation. Additional Funding by Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer, the Friends of Idaho Public Television, Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Nothing But the Truth

Season 5 Episode 2 | 26m 49sVideo has Closed Captions

In Idaho’s early days, disputes were settled by knives, guns and fists. It took a few zealous advocates to ensure that the rule of law prevailed over vigilantism in the 1800s; and it takes the same dogged commitment to ensure justice in our time. Two sensational Idaho murder cases 100 years apart remind us about the enduring power of truth, justice and fact-finding.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Idaho Experience

Idaho Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANNOUNCER: Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the J.A.

and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.

Making Idaho a place to learn, thrive and prosper.

With additional support from Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, and Judy and Steve Meyer, the Friends of Idaho Public Television, the Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

[MUSIC] NARRATOR: In the early days of Idaho, justice often was dispensed with a fist or a knife or a gun.

DAVID METCALF: Claim jumping was just common and you really needed some enforcement back then.

And that was the Bowie knife.

And if you didn't have that, you were in trouble.

NARRATOR: James Hawley was a big guy and he could defend his Idaho City mining claims.

But he knew there was a better way, so he studied the law and became a lawyer in 1871.

METCALF: He had a vision of what he wanted to do.

It was instill the rule of law in this wild territory.

It was a near obsession with the rule of law.

NARRATOR: Hawley's most famous obsession was Diamondfield Jack Davis, a tough-talking enforcer accused of killing two sheepherders on the Idaho range in 1896.

MAX BLACK: One of the jurors was quoted as saying it didn't matter whether Jack Davis was guilty or innocent, he should have been hung on general principles.

NARRATOR: Vigilantism is no longer an accepted remedy for resolving our disputes.

And even under the rule of law, it can still take an obsessive commitment to see that truth and justice win out.

GREG SILVEY: Sometimes in order for justice to prevail, it just takes a single-mindedness, the zealousness, when your friends and family are tired of hearing you talk about that case anymore.

NARRATOR: Today, truth can get ignored or discarded for political expediency, and facts we don't want to hear are dismissed as "fake news."

But proof is still required in the courtroom.

CATHY SILAK: Those conflicts are not solved by who has the most money, who can post the most items on social media.

Those disputes are solved in a courtroom with dignity, with decorum, following rules.

NARRATOR: With rules of evidence and independent review, the courts are one place where our society still emphasizes facts over everything else.

Even when the facts are as implausible as any storyteller's imagination.

BLACK: There is a Native American saying that says a story stalks a writer.

And if you are found worthy, your responsibility is to give the story verse.

And I have become obsessed.

NARRATOR: Obsessed with the truth, and "Nothing But the Truth," on Idaho Experience.

[MUSIC] [MUSIC] BLACK: Jack Davis was a braggart and left people with the impression that he was a real tough guy.

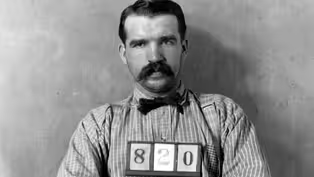

NARRATOR: Diamondfield Jack Davis.

He was no icon of justice.

He made his living as an enforcer on the biggest cattle ranches in Nevada and Idaho, threatening, and once even wounding, sheepherders who were pushing onto traditional cattle range.

METCALF: So his job was to intimidate sheepherders, even to the point of assault.

So it was a job for a bully, and he was a bully.

NARRATOR: When sheepherders Daniel Cummings and John Wilson were found shot to death at their camp on the cattlemen's side of "Deadline Ridge" in February 1896, there was one obvious suspect.

METCALF: Everybody knew that Diamondfield Jack had been threatening sheepherders and immediately the suspicion focused on Diamondfield.

NARRATOR: Jackson Lee Davis.

Nobody knew his real age, or if that was even his real name.

He told so many stories so often that biographers can't sort out the lies and legends.

BLACK: In four or five different testimonies, he gave birthplaces of four or five different places.

NARRATOR: We do know that Jack Davis got the name Diamondfield after leaving Silver City, in hopes of striking it rich at an Idaho diamond mine.

That was a bust, so he drifted to work on cattle ranches.

At the Shoe Soul Ranch near Rock Creek, a cowboy thought he'd insult Jack for being gullible.

But Jack Davis liked the fancy sound of "Diamondfield Jack" and kept the name.

Fanciful nickname or not, he'd be ignored by history if not for the range war between cattlemen and sheepmen in the late 1800s.

This high-stakes case attracted Idaho's two best-known lawyers.

William Borah was hired by the sheepherders to aid the Cassia County prosecution.

METCALF: This is before his days as a senator and world fame.

He's 32, I think, and he wants to make a name for himself.

And this is a really high-publicity case because this is cattle versus sheep.

NARRATOR: Borah would become a U.S. senator 10 years later and one of the most powerful men in America.

James Hawley, who would soon be Boise's mayor and then Idaho governor, was already established as the most prominent criminal lawyer in Idaho and the founder of a law firm that bears his name today.

Hawley and Borah would later team up as prosecutors – allied against Clarence Darrow – in the celebrated Trial of the Century, following the murder of Gov.

Frank Steunenberg.

Hawley was hired by the Sparks-Harrell cattle company to defend Diamondfield Jack.

Born in Iowa in 1847, Hawley came to Idaho as a teenager to mine gold.

He made enough money to attend college, then trained for the law … starting his practice in a tent in Idaho City in the 1870s.

By 1896, he'd defended or prosecuted more murder cases than any other lawyer in the state.

Diamondfield Jack's trial was in the Cassia County Courthouse, across the street from the primitive county jail in Albion.

The murdered men were local, from Mormon sheep families, and the jurors' allegiances were with the sheepmen.

METCALF: The religious atmosphere was against him.

The sheepherders were all against him.

And now he's looking at a jury that's composed almost entirely of people who would love to see him swing.

NARRATOR: The case was weak and circumstantial, and the trial sloppy.

Important evidence was misplaced, or lost.

Tests on the weapons and bullets were amateurish.

The newspapers were mostly against Jack, and his own outbursts, even at the judge, did not help his cause.

METCALF: In defending Diamondfield, James Hawley felt he was up against not only the state of Idaho but also the sheep industry, the Idaho Statesman newspaper, the Mormon Church and even his own client.

NARRATOR: The sheepherders were probably killed in their wagon on Feb. 4, 1896.

Diamondfield Jack and his alleged accomplice, Fred Gleason, were seen miles away that day – at the Brown Ranch at breakfast and at the Boar's Nest Ranch around lunchtime.

METCALF: What Borah had to show was that Diamondfield Jack and Fred Gleason road 55 miles in five hours and killed these guys.

And that was just impossible.

Despite the fact that Borah got some people to say it was possible in the trial, Hawley knew it wasn't.

Hawley also had a real suspicion all along that somebody in the Sparks-Harrell organization committed those murders, and not Diamondfield.

NARRATOR: The jury quickly convicted Diamondfield Jack, although Hawley got Gleason acquitted on the same evidence.

The judge sentenced Jack Davis to hang.

Idaho court dockets reveal Hawley's efforts: Motions, appeals, hearings, in the lower courts, the Idaho Supreme Court, the Idaho Pardon Board, even the U.S. Supreme Court.

He kept Diamondfield's case – and Diamondfield – alive.

BLACK: Listen to this: He appeared before the Board of Pardons 35 times.

METCALF: The gallows are being built in Albion and he's going to be hung.

BLACK: He was ready.

They fed him his last meal.

METCALF: The 9th Circuit Court of Appeals issues a stay, but he's still in jail – it's just been a stay.

NARRATOR: Hawley had won a delay, so he and another lawyer rode the circuit of Sparks-Harrell ranches, interviewing and investigating.

And then, a breakthrough.

James Bower, the respected Sparks-Harrell superintendent, confessed that he and cowboy Jeff Gray had killed the sheepherders, during a scuffle, in what they said was self-defense.

METCALF: So what did the pardon board do?

Set him free?

No, they didn't set him free.

They said, we will take the death penalty off the table, but he'll be in jail for life.

And for what?

BLACK: They rescinded the death penalty, but changed it to life in prison.

I mean, that's how prejudiced the whole operation was.

METCALF: The pardons board made that decision on the day that he was to be hung.

NARRATOR: Worried that Diamondfield Jack's enemies would plot an ambush, James Hawley sent two riders, including cowboy Willis Sears, to make sure word of the reprieve reached the sheriff in Albion in time.

METCALF: Sears would say in 1955 the actual noose was around Diamondfield's neck when I arrived, and they removed the noose and put him back in jail.

Finally, Governor Hunt pardons him and he goes free.

NARRATOR: Sentenced to death seven times, twice coming within hours of hanging, after five years, Diamondfield Jack Davis walked out of jail a free man.

[MUSIC] NARRATOR: Diamondfield Jack was a free man – and a young man.

In 1902, he was probably no more than 30 years old, with much life left to live.

With a grubstake from one of his former prosecutors, he left for Nevada.

This laughable diamond miner soon struck gold, amassing a fortune in Nevada mines.

He even founded his own mining town between Reno and Las Vegas, named Diamondfield, of course.

METCALF: He becomes this whole different person.

Within a year or two, he had a noose around his neck and now he's a reputable businessman.

NARRATOR: The papers chronicled his Nevada exploits.

His rich and powerful partners included a U.S. senator and Gov.

John Sparks, his old boss at the Sparks-Herrell cattle company.

He carried on a famous affair with Diamondtooth Lil, a madam who also spent time in Boise, although they parted on less-than-friendly terms.

Always volatile, Davis still was loyal to his friends and rewarded the men who'd helped him win his freedom.

Extravagant, boastful, erratic, Diamondfield Jack lost his fortune and ended up drifting around the West, hoping to strike it rich again.

In Las Vegas, he accidentally stepped in front of a taxi cab and died in 1949.

[MUSIC] NARRATOR: Max Black is not someone you'd expect to become fixated on an alleged outlaw.

For 20 years, he was a member of the Idaho Legislature.

He got interested in Diamondfield Jack's story as an insurance agent who traveled regularly to Albion.

One night, researching the trial transcripts, Max realized that not all the bullets from the fatal shooting had been recovered in 1896.

BLACK: There were three shots fired.

When I was reading it, I wrote in the column about this testimony and I got it, still in there in red pen, it said.

"So the bullet is still there."

NARRATOR: After his years of research, Max started to wonder: Could he find the site of the shooting?

Using the survey records commissioned for the 1897 trial, an engineer friend mapped GPS points for Black to investigate.

And Max found a key ally in his obsession.

KUNKEL: Max pulled in my driveway one day and I had no clue who he was.

And he says, "Do you know where the sheepherder killing site was?"

NARRATOR: Alex Kunkel grew up on Duck Springs Ranch, near Rogerson.

Over the years, old-timers had pointed out the area of the shooting, a few miles from his family's home.

Kunkel had heard stories about James Bower and Jeff Gray stopping nearby to trade a bloody coat for a clean one.

Kunkel even found casings that he believes are from Diamondfield Jack's target practice.

KUNKEL: So I became extremely interested the day that, that Max pulled in my driveway.

NARRATOR: With Max's research and Alex's memories, they narrowed their search to a flat spot overlooking the range, with a rock pile that matched written descriptions of the sheep camp.

BLACK: And from this site, we started to look around the area.

And on the left-hand side on the front of the wagon, we found some tin cans.

And then on this side, Alex found items that would pertain to a wagon.

KUNKEL: So this is the cart stake pockets to the covered wagon, the oak sticks that make the hoop for the canvas.

They come around and lock in.

And we found four of these on this site.

It's extremely unusual to find wagon parts in an open area where there's no homestead around.

NARRATOR: Max worked out the position of the wagon.

Knowing that the men had wrestled as Bower's gun fired, Max calculated the trajectory of a bullet that had left a hole in a saddle 30 feet away.

Then searched the ground around one sagebrush, then another.

BLACK: And put my metal detector down and bingo, there was metal.

So I just knelt down and scraped the dirt off, down to find what it was indicating, and there's this bullet.

That's how accurate that surveyor was, and put us pinpoint where the wagon sat.

You know to try to describe the feeling of actually finding that bullet, was ecstatic.

KUNKEL: So with the bullet and the cart stakes, we're pretty sure that we're setting on the spot of the sheepherder killing site.

NARRATOR: The bullet matched .44-caliber casings found in 1896.

For Max, it confirmed Bower's account of the shooting – and Diamondfield Jack's innocence.

BLACK: There's no question in my mind that Bower and Gray were there and that's how it happened.

NARRATOR: Max documented his search in a book in 2013.

He includes a postscript about an encounter with a gun-collector friend that almost defies belief.

BLACK: And I said, did I ever tell you that I found a bullet from the site?

So I told him this story.

And while I was telling it to him, he stopped and said, "Max, where did you say this happened again?"

And I said well, about six and half miles southeast of Rogerson, Idaho.

So he looked at me again and he said "Max, I've got that gun."

And I said, what would make you think you have that gun?

NARRATOR: A badly rusted Colt revolver, with a Bakelite grip.

One of less than 3,000 made in England between 1878 and 1925, for an under-the-shoulder holster like James Bower used.

The pistol had been found by a family of collectors and treasure hunters who had once done work on Duck Springs Ranch.

Kunkel: As it turns out, there's been family members of the Gray family tell me that the family says, as they rode past Duck Springs, they put the pistol in the spring.

BLACK: And they asked Bower, in testimony, where is the gun?

He's, well, I lost it.

Where did you lose it?

Out in the desert.

I think he threw the gun in the water to get rid of it.

You can't say 100 percent sure, but I would bet pretty heavily on it that that's the gun.

And I know that's the bullet, lying right where they said it was a hundred years later.

[MUSIC] [MUSIC] NARRATOR: It's been well over 100 years since Diamondfield Jack's conviction.

The law, technology and court procedures have changed.

Society now recognizes that faulty scientific analysis, forced confessions and jailhouse informants are common factors in wrongful convictions.

GREG SILVEY: Defense attorneys have always known there are wrongful convictions.

The rest of the world did not know that until there were DNA exonerations.

We've gone from people just absolutely not believing it, to, now, now it's a force.

NARRATOR: One thing has not changed in the 125 years since Diamondfield Jack was freed from that Albion jail and that's the power of a determined lawyer who doggedly advocates for the truth.

SILVEY: Sometimes in order for justice to prevail, it just takes a single-mindedness, the zealousness when your friends and family are tired of hearing you talk about that case anymore.

Yes, Mr. Fain was, he was particularly lucky to have that sort of attorney that could stick with it.

NARRATOR: Charles Fain spent 18 years on death row, convicted in the 1982 rape and killing of nine-year-old Daralyn Johnson.

Fain wasn't released from prison until 2001 when he was exonerated by DNA evidence, thanks to a team of lawyers led by Fred Hoopes.

METCALF: The Fain case and the Diamondfield case have a lot of parallels.

The public is clamoring for an arrest and the evidence was just not there.

Fred Hoopes became a zealous advocate for Charles Fain.

He saw the thinness of the evidence.

He saw that Charles didn't do this.

He was just a dog with a bone, just like Hawley was for Diamondfield.

NARRATOR: In 2021, the Idaho Legislature created a fund to compensate people wrongfully sent to prison, with payments of up to $75,000 a year.

JIM JONES: The system let 'em down and they deserve to have compensation.

NARRATOR: As Attorney General, Jim Jones argued against Fain's appeal, in the belief that the FBI evidence was reliable.

JONES: I was just absolutely flabbergasted when a story came out saying that the FBI had fudged the DNA analysis.

They had essentially betrayed the state.

CATHY SILAK: Judges will make a correction when it's needed, and that's an important safety valve for society.

And that's why we talk about a justice system.

It is a system, not just of people, but of these very important concepts.

NARRATOR: Gregory Moeller, an Idaho Supreme Court justice, was a young lawyer fresh out of law school in 1991 when he took on an Eastern Idaho murder case that would change his perspective on the law.

GREGORY MOELLER: We realized that we had what some might consider every attorney's dream and yet every attorney's worst nightmare.

We were representing an innocent man in a first-degree murder case.

NARRATOR: Rauland Grube was convicted, but after multiple appeals, he was freed in 2006, when a federal judge ruled that he had been denied a fair trial.

MOELLER: The burden that you feel upon you when representing an innocent man in a capital case is something that just stays with you.

It's just literally having someone's life in your hands and knowing that their future is going to depend upon your ability to do your job.

NARRATOR: Moeller decided to become a lawyer when he was in high school, after discovering "To Kill a Mockingbird."

The 1960 story by Harper Lee tells of Atticus Finch, a lawyer in the Deep South who represents Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of raping a white woman.

In 2009, Moeller gave a speech on how the book influenced the course of his life and career.

MOELLER: Here I was, a young man inspired to become an attorney by a woman who wrote a book about a case.

I did become an attorney and I got a case similar to that in the book.

I gave a speech about it.

The speech somehow found its way to the woman that wrote the book, and then she sent me a copy of the book to thank me for what I had done.

For reasons I never anticipated or sought, there's a connection between me and Harper Lee and the book that she wrote that inspired me to become an attorney and, eventually, become a justice on the Supreme Court.

NARRATOR: Tom Robinson and Atticus Finch, Charles Fain and Fred Hoopes, Diamondfield Jack and James Hawley, stories that remind us of the power of finding the facts and pursuing the truth.

[MUSIC] [MUSIC] ANNOUNCER: Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the J.A.

and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.

Making Idaho a place to learn, thrive and prosper.

With additional support from Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, and Judy and Steve Meyer, the Friends of Idaho Public Television, the Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Introduction to "Nothing But the Truth"

Clip: S5 Ep2 | 3m 10s | Introduction to "Nothing But the Truth" (3m 10s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major Funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation. Additional Funding by Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer, the Friends of Idaho Public Television, Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.