Sweet Idaho Special

Season 6 Episode 5 | 36m 34sVideo has Closed Captions

Learns the secrets of Idaho’s iconic sweet-treat historic entrepreneurs.

There is just something about chocolate, ice cream, bonbons, and pie. Learn the secrets of the Idaho Candy Company, Lee's Candies, Florence’s Chocolates, and Reed’s Dairy’s ice cream. Find the best pies in North Idaho and the sweetest spot in Sweet, Idaho. Idaho Experience: Sweet Idaho looks at the history of some of Idaho's “sweet” companies and how they make these classic goodies.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer. Additional funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson...

Sweet Idaho Special

Season 6 Episode 5 | 36m 34sVideo has Closed Captions

There is just something about chocolate, ice cream, bonbons, and pie. Learn the secrets of the Idaho Candy Company, Lee's Candies, Florence’s Chocolates, and Reed’s Dairy’s ice cream. Find the best pies in North Idaho and the sweetest spot in Sweet, Idaho. Idaho Experience: Sweet Idaho looks at the history of some of Idaho's “sweet” companies and how they make these classic goodies.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Idaho Experience

Idaho Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[Narrator] Idaho Experience is made possible with funding from the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation devoted to preserving the spirit of Idaho.

From Anne Voilleque and Louise Nelson from Judy and Steve Meyer with additional support from the J.A.

and Katherine Albertson Family Foundation, the Friends of Idaho Public Television, the Idaho Public Television Endowment, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

[Dave Wagers] You start talking about candy and everybody's they light up.

[Brian Manwaring] Well, chocolate has always kind of been one of those foods that just makes you feel good.

[Alan Reed] You know, ice cream is one of those treats that there's so many different flavors.

And so your choices are huge.

[Elizabeth Salmeri] I like makin making peach pies.

I just I love the freshness.

And it reminds me of summer.

[Narrator] Pie, Candy bars, bonbons, ice cream.

Idahoans love their sweets.

[Wagers] The Idaho Spud Bar, as far as I know, there's not another bar on the market like it.

[Manwaring] A lot of families, you know, a lot of the kids that are coming in the new generation are saying, my parents used to buy this.

And and it's just a family tradition.

And I think that's what makes it nostalgic.

[Narrator] And for some, creating something sweet is a way of bringing people together.

[John French] Seeing people enjoy themselves, it's a very rewarding feeling.

[Katie Fernandez] It's kind of And now kind of brings me back to Grandma's kitchen.

[Narrator] Idaho Traditions Old and New.

Coming up on Idaho Experience.

{Narrator] Candy bars as we know them today are a result of the industrial revolution.

New fangled steam powered machines could turn out enough product for greater distribution and easier access to quality sugar helped.

With more products around Americans, consumed candy as a regular part of their diet, and Idahoans were no different.

Thomas Smith saw the opportunity and established the Idaho Candy Company in 1901.

But he needed help.

[Dave Wagers] By 1909, a family came to Boise, and it was the Addams Family, and they had come from California.

They had a little bit of money, and he got them as investors in the factory.

And that's when the candy company really started to grow.

[Narrator] At the time, there were no national candy bar companies.

Transporting chocolate was tricky and refrigeration was expensive.

So each part of the country had its own regional candy company all trying to survive.

[Wagers] I think all candy manufacturers, they were looking for something interesting, a hook and T.O.

Smith was no different.

[Narrator] Smith's great idea, The Idaho Spud Bar.

[Wagers] It was a round oval bar so it looked like a potato.

I mean, was that kind of size.

Not maybe not quite that big, but it was bigger than it is today.

And they had one half of a marshmallow that looks much like our bar does today.

And then they would have another half and they would coat both halves with chocolate and they would put those together by hand.

And so you'd have kind of a semicircle, you know, ovoid of marshmallow with a layer of chocolate, dark chocolate in the center and another circle on the bottom.

And then they would coat that whole thing with chocolate and that whole thing with coconut.

And the coconut was meant to be the eyes of the potato.

And then you had this, you know, interior that was a little brownish grayish, kind of a weird color for candy, really, but that made it kind of look like a potato.

[Narrator] At $0.05 a bar, it was on the expensive side.

But the Idaho Spud was a hit right from the start.

It was first marketed as a health bar because of one unusual ingredient.

[Wagers] It's a different kind of marshmallow.

And so the marshmallow we use in the Idaho Spud bar, it's called a grained marshmallow.

It's made with agar agar instead of gelatin.

And agar agar is one of our most expensive ingredients, and it's actually made from seaweed.

I do not know how they got it here in the 1900s, because it seems like a difficult ingredient to get, but it made the candy bar different.

[Narrator] With the spud bar, the cherry cocktail, and the old faithful, as well as punch boards and cigrettes, The Idaho Candy Company thrived.

[Wagers] It became a pretty good business of size, especially in the twenties and thirties.

They had close to 100 employees.

I mean, they were very much a regional candy manufacturer supplying the area with candy.

[Narrator] The Idaho Candy Company moved to its current downtown Boise factory in the early 1920s.

Women in heels and dresses, hand dipping candy made up a large part of the workforce.

But by the fifties and sixties, the industry had changed.

[Wagers] As candy brands started getting more national.

They started taking more space on the store shelves.

At one point, I think we had probably 40 or 50 different candy bars that we were making and now we're down to 4.

[Narrator] In 1984, John Wagers bought the Idaho Candy Company, and his son Dave took over as president in 1991.

[Wagers] Yeah, I went to candy school, actually at University of Wisconsin, and I learned how to make candy.

And I learned, you know, I learned a lot of the history of Idaho Candy, just being in the factory and working with the employees.

[Narrator] And he started to make changes.

[Wagers] We did a contest through The Idaho Statesman and said, okay, let's create a candy bar.

[Narrator] And the Huckleberry Gem was born.

But Wagers makes changes very gently.

[Wagers] Idaho Candy Company, it's an old, nostalgic candy company.

You know, we're still hand stretching all of our peanut brittle.

[Narrator] The Idaho Candy Company factory and storefront is a fixed landmark in downtown Boise.

It's probably the only factory in downtown, and the building is worth more than the company.

Using basically the same process and much of the same equipment, Wagers and his crew take two days to make a batch of the famous Idaho Spud bars.

[Wagers] On the first day we make the marshmallow, we cook up corn syrup and sugar and agar agar and we put those into a large marshmallow whipper, it whips them up for about 4 or 5 minutes.

We add an egg whites, which is what does the aeration of the marshmallow.

It gives it the lightness, which all marshmallow has some aeration to it, or else it wouldn't be light and fluffy.

And then we whip that for about 5 minutes.

We add in some flavors.

And the way you make the marshmallow, it's called the starch, that method of making candy.

So you start with a tray of corn starch, and then you put a mold down into it.

And so the starch bad method of making candy is very prevalent today.

Anything that's jelly or gummy is made an a machine that I call a starch mogul.

And that's a big machine that makes starch candy.

So.

And we push down a mold that has 36 Idaho spud bars upside down into that train, at least 36 depressions in the mold.

And then it goes through and you deposit marshmallow into that.

And then that sets for a day.

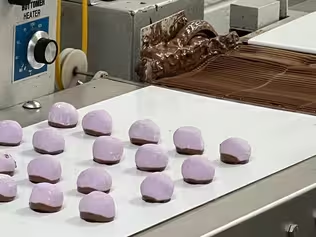

And so we take those marshmallow centers and we send them down in the elevator and they go down in trays, and then we put them on a belt.

We run it through the chocolate enrober.

It coats that that funny potato shaped marshmallow with chocolate.

And then it goes right onto a coconut enrober, which I've never seen another coconut enrober.

As far as I know.

We may have the only one in the U.S. and it transfers onto a bed of coconut.

And so that gets coconut on the bottom.

And then there's a waterfall of coconut that falls down and falls on that bar as it as it travels through this coconut enrober.

And then at the end of the coconut enrober, there's a blower that blows off the excess coconut and then that goes back into the base for the next part.

And then it goes into a long cooling tunnel, about a 65 foot long cooling tunnel, which then cools the chocolate and it sets up.

And by the time it gets to the end of that cooling tunnel, it's ready to be packaged and it goes right onto a packaging machine.

We package about 100 bars a minute.

[Narrator] And they still hand make a number of other products.

[Wagers] When you buy our peanut brittle or you buy our butter toffee, you can look at it and somebody can say, My grandma could have made this.

And it's more that feel versus where maybe if you buy a Hershey bar, every single one is identical, Right?

And that's what they want and that's then that's a great thing.

And I'm happy that they do it that way.

That's not what I want from my Owyhee Butter Toffee.

I want uneven edges.

I want a broken I want it to look handmade.

I want it to look, you know, some little bit thicker in some places, a little bit thinner in other places.

Sometimes I think we get too caught up in everything being perfect and sometimes it's the non perfect stuff that can make life good.

And you know, that has been one of the blessings of my job is, is people, they want to understand it.

It's exciting!

When you start talking about candy and everybody's they light up, you know, everybody understands candy.

Kids love it.

Adults love it.

And it's an iconic piece of Idaho that my family's been lucky enough to be a part of.

We've always felt like we're just the caretakers of this company for Idaho because it's been around so long and it's so much a part of people's stories.

[Narrator] French Chocolatiers invented chocolate bonbons for royalty.

They were bite sized candies covered in chocolate and placed in ornate containers.

And they were only for the elite.

By the late 1800s, chocolates no longer had to be made by hand in small batches.

Mechanized equipment could turn out bonbons by the hundreds, but many people still preferred the taste of chocolates crafted by artisans.

And there was just something special about getting a box of your favorites.

[Katie Fernandez] I think it's also just kind of that old fashion um .

.

.

nostalgic feeling of going into an old fashioned candy store and picking out something that, you know, has been around for, you know, generations and decades.

Plus I just think Candy makes people happy.

I think some a good high quality piece of chocolate makes you feel good.

[Narrator] Idaho's oldest continuing bonbon business is thought to be Lee's Candies in Boise.

In eastern Idaho, it was Florence Manwaring who brought her skills to the region.

[Brian Manwaring] My mom, she actually worked for a candy company at one time for Allen Wertz.

She worked for them and then she also used to make candy with her mother.

And so it was kind of a bonding time for them to be able to to share with each other.

And so they would mess around with the recipes and add and take away some things and and use different ingredients.

[Narrator] And that is what makes these hometown candy stores different.

While National Chocolate companies provide uniformity, local chocolatiers each have their own approach to creating their tiny works of edible art.

[Katie] So we always start with sugar.

Sugar, surprise, surprise is the main ingredient in all the candy we make.

So we start with the syrup and we cook it to temperature 242 to 240 degrees.

And then we bring it over to our candy mixer.

And where we pour the syrup into the mixer.

We let it cool for a few minutes and then as it's mixing, we add the ingredients that make each center specific to the flavor we're going for.

Today, we made Huckleberry Creams.

We added mazetta, which is basically meringue is egg whites and glucose that kind of whip together.

So it's nice and fluffy.

It gives our our candy a nice creamy texture, and then we let it mix until it's just the right consistency.

Then we pull it out of the candy mixer and we place it in loaves on our table, and then we all stand around for about an hour or an hour and a half as a team.

And we individually hand roll each center so that is the right shape and size.

Once that happens, we take it into our enrobing room and we put it on on the belt.

It gets a bottom and then it gets another bottom and then it goes through our chocolate fountain until it's coated in chocolate.

It goes through the cooling tunnel.

And then we we take it off the belt and store it till we need it.

[Narrator] The chocolates at Florence's are made in much the same way.

[Brian] We use butter and real cream and sugar all the all the really yummy stuff.

We do about 70 pound batches at a time.

It's taken and rolled by hand into the little centers or balls, is what we call them.

And then we put a bottom of chocolate on them.

And basically that's strengthens the chocolate so that when you pull it off the paper, then the bottom doesn't fall out.

[Narrator] Some chocolates in both places are still hand dipped.

[Michelle Manwaring] It's quite a trick when you start dipping.

It takes about 3 to 6 months to learn how to work the chocolate properly so that you're not ending up with a product that has a lot of marbling or feathering in it.

So there is an actual specific way Florence wanted all of us to learn.

And so as you put the fondant on your hands and then you have to just finesse the top with your fingers together.

[Narrator] Next, she swirls a chocolate sign, the symbol that reveals the kind of filling inside.

[Michelle] It's quite the trick, and it takes a while to learn how to sign.

So you have to get a string of chocolate and maneuver the that string of chocolate to make whatever letter or design needs to be on top of the chocolate itself.

[Narrator] And just so you know, there is no standardized code for chocolate bonbons.

Every maker has their own way to identify what's inside.

[Brian] Chocolate is very labor intensive.

I don't think people realize how much work goes into making chocolates.

We usually go around anywhere between 30 and 40,000 pounds of chocolate a year of of raw chocolate.

[Katie] So our best sellers are our orange creams and then probably our Monte Carlo.

That's the one with the soft caramel center and the vanilla creme.

And then our famous Victoria Cream, which is walnuts and butter rum flavored.

[Narrator] Florence's top two sellers are Princess Michelle's and Caramels.

But all the candy makers say they are selling more than chocolate.

They're selling smiles.

[Katie] Hey .

.

.

who wants to try some?

[Michelle] But also, I think there's something to do with just emotional connection with it.

It might be something with a memory of something that has a child.

You know, we get that a lot here at the store that we'll have customers that come in said, you know, Christmas morning was not complete until they brought out Florence's candies.

[Katie] All right, let's do this.

There is not one day that goes by that I don't have somebody come in with a story about how Lee's fit into their life.

That their grandma used to buy in, you know, Lee's Candies every holiday.

And now they're doing it.

And then their mom took it over and now they're doing that for their kids.

[Brian] Well, chocolate has always kind of been one of those foods that just makes you feel good.

When they first walk in the doors, they go, Oh, this smells so good in here.

It smells like chocolate.

And it puts a smile on their face just by the smell of chocolate.

And that's that's what makes us happy.

That makes us feel like we're doing our job.

So.

And doing it well.

[Narrator] What's more American than ice cream?

One quaint but fictitious story credits Martha Washington with inventing ice cream after she left a bowl of cream outdoors to freeze overnight.

While George Washington did love ice cream versions of this sweet treat can be found back as far as 300 BCE.

Ancient Greeks and Romans would climb mountains to harvest ice.

They'd mix ice with wine or honey like an early version of a Slurpee.

The ancient Chinese are credited for the first use of dairy in a frozen treat.

Their recipe called for milk, flour and camphor.

Though ice cream remains a worldwide favorite, it's an American institution.

On Ellis Island, officials even gave a few lucky immigrants ice cream as part of their first American meal.

And after the ice cream churn was patented in 1843, anyone could make it at home.

And in Idaho, where better to get the milk for the ice cream than from Reeds dairy?

[Alan Reed] It originally started around 1955 My uncle and and my dad and and the other brother, they all farmed together and Larry started running the dairy side of the business.

And then we had a another processing facility here in town that was bottling the milk for us and cartons.

And then in 1962, we put in our own equipment and started bottling our own milk.

[Narrator] 20 years later, the next generation of Reeds came up with a new product honoring an old family tradition.

[Alan] I looked at it at the situation that we were in, and we had a lot of cream from separating it from the milk for low fat milk.

And and we were selling that to another processor.

And I just thought, why are we not making our own ice cream?

Because my grandmother was a big ice cream maker.

And so any party that we would have family get together, she was always making ice cream.

And and it was really good stuff.

[Narrator] But making ice cream just as good as his grandmother's wasn't easy.

[Alan] We were at least six months working on formulas for the type of ice cream we wanted because we just wanted cream, milk and sugar.

And then we moved forward to creating flavors and packaging, and off we went.

[Narrator] And it was an immediate hit.

[Alan] Well, the first thing we have to do is make the mix.

And so in our processing plant, we blend the cream, milk and sugar.

We stir in the cookies and caramel and nuts and whatever ingredient it calls for for that flavor into the container.

And that's all blended together and is pasteurized and homogenized.

And then we draw that out.

It's like a really stiff soft serve temperature, and we put five gallons at a time in our batch freezers, and it's just like your homemade freezer, except we're using freon instead of ice and salt.

[Narrator] Reed's Dairy now sells more than 80 flavors of ice cream, but the company made national news with one of their more unusual varieties.

In the mid 1980s Reed's invented something you might expect from this eastern Idaho company, a potato ice cream.

[Alan] The potato ice cream was a product that we made sugar free.

There was no refined sugar and it was low fat.

And we used the potato flakes to help with the texture.

And we also realized through some special processing that we could get the starch in potatoes to help us with the sweetener.

[Narrator] The formula for potato ice cream was eventually sold to another company, but Alan still uses potato flakes.

[Alan] Originally we were, making our chocolate milk.

We would put nonfat milk powder in to help with the texture to thicken it up.

And I got looking at non-fat milk powder was costing me over a dollar a pound.

Potato flakes at the time were around $0.35 a pound.

And I thought, you know, I figured this out with the ice cream, I think I can figure out how to make it run with chocolate milk.

[Narrator] Reed's dairy sells a variety of cheese milk as well as ice cream.

And the top selling flavor?

[Alan] Vanilla.

Yeah, vanilla is our top flavor.

Huckleberry is right there, close to it.

In fact, a couple of years ago, I thought Huckleberry was going to overtake vanilla, but Vanilla hung in there.

And so we make more vanilla than the other flavors.

[Narrator] So just what is it about ice cream?

The average American consumes more than 12 pounds each year.

[Alan] You know, ice cream is one of those treats that there's so many different flavors.

And so your choices are huge.

[Narrator] And like candy bars and bonbons, ice cream invokes a sense of nostalgia.

[Alan] You know, it just makes a great family time sitting around and having an ice cream cone.

[Narrator] And what goes better with ice cream than pie?

Ask well-traveled Idahoans about the best place for a piece of pie and it's not long until you hear about The Pie Safe.

The bakery in Deary isn't the oldest or biggest or fanciest bakery you can visit.

It's out of the way, so you have to want to get there.

But in it's short history.

It has become a community gathering spot and a word of mouth destination.

[John French] It's a it's a neat feeling.

I would say That's one of the most rewarding things about having a business like this and being a part of something like this.

Seeing people enjoy themselves and have a place to bring family and friends when they're visiting is a very rewarding feeling.

[Narrator] Loyal customers bring friends .

.

.

of all kinds to The Pie Safe.

They come from as far away as Moscow or Lewiston.

And though Deary has just over 500 residents, the line for Pie Safe goodies can stretch out the door.

[John] Especially in the summertime, we meet a lot of people from all over the country and Canada from all over the world.

[Andrew Cunningham] So, it's not just people from here, but it really introduces a lot of things to the community here that the people like.

And so you get to see a lot of neat things.

[Ron Halseth] It's an interesting place to come.

It's just a good place to sit back here in the corner, we can watch the people and we're talking.

So.

[John] This building came up for sale.

We bought it about seven years ago, did an extensive renovation to it.

We were looking for a place to start a little bakery and retail crafts shop.

My wife was a baker and has kind of always dreamed of having a little bakery and partnered with our sister company, Brush Creek Creamery.

And so they occupied part of the space here.

And we opened in the summer of 2016 and we had about 30 seats at the time and in our dining room, and we have grown significantly since then.

[Narrator] The name Pie Safe refers, of course, to the old timey cabinets in which bakers cooled and stored their pies.

Owner John French picked the name before he connected it to the fact that the old car dealership had a real safe, which is now part of the pizza oven.

So The Pie Safe has a true to life pizza-pie-safe?

[Ron] Well, you know, this used to be a service station.

Bill Anderson owned it.

And before that, Wylie's, just like that safe.

It's got the name Wylie Motor on it.

And they did a beautiful job fixing it up like those beams back there and that pizza outfit.

That come off of the schoolhouse up there, the gym.

[John} So it was built in 1922.

And it was a Ford garage originally.

So they sold new Ford Model T's out of the showroom there in the front.

And this whole back part where we are now, and it was the repair shop.

We have renovated the building across the street here.

It was an old appliance store in the fifties and sixties.

It's now like a handcrafts weaving.

So any kind of shop.

We renovated the old train depot just up the street here, an old train car we've turned into a, um, Airbnb.

[Narrator] The Pie Safe owners and many of its employees are members of Idaho Heritage, a back to basics faith community, often mistaken for Mennonites, but with its roots in Texas Anabaptism.

It emphasizes agrarian values and handmade crafts and food and members prized traditional values, simplicity, family, self-sufficiency and craftsmanship.

The loggers and farmers in Deary were a little wary when members started showing up in the early 2000s.

[Ron] Yeah, yeah, there was, I think pretty much all that is pretty much changed now.

There is a good group of people, but when they come here, it didn't take long to where they fit right in with everybody else.

Worked out pretty good for Deary and us.

So [Narrator] one recent example, an old fashioned barn raising, reassembling an Amish barn, relocated from Pennsylvania.

[John} You know, I think people are looking for, I'm looking for wholeness in life.

I think we see a lot of Western culture that detaches where you work, how you eat, where you live, how you act, what you say is all kind of can be separate categories.

And we're looking for more of a whole lifestyle where those things are more in alignment with each other.

So that would encompass everything from what you're eating, making food from scratch, growing food, things like that that helped just ground you.

And we try to maintain a pleasant, fun, healthy, exciting work environment.

And that attracts people.

[Elizabeth Salmeri] It's something bigger than just one individual can do.

It's all of us together working together that makes this place.

what it is.

It's not just one person doing their job.

And so just to be a part of something bigger than whatever you're doing on your own, to me, that's that's pretty neat.

You can be a part of something that lots of people from all over the world are coming to, and it's a privilege to be a part of it.

[Narrator] Oh, and about those Pie Safe pies.

[John] So twice a week we bake pies.

We bake them on Tuesdays and Friday mornings.

Right now, we're making about 35 to 40 pies a week.

We seasonally have different types of pie.

We try to use peaches and strawberries and rhubarb and apples.

And depending on the season, pecan, pumpkin more for Thanksgiving and such.

[Elizabeth] We're making v pies, mixed berry pies.

Oh, there's those pecan pies.

I have an order for a key lime pie.

So we're making those.

Peach pies, Blueberry peach pies.

I think that's it for the pies.

[Narrator] And here's a baker's secret.

There's a pie crust code.

[Elizabeth] We have different patterns for the different pies that we make.

The cherry pie is squares for the lattice.

Mixed berry is diagonals.

And then the apple.

We just put a top on the apple.

So people at the front, they know the difference between the pies.

So I like making peach pies.

I just.

I love the freshness and reminds me of Summer and I like peach pies the best I think.

[Andrew] The pecan is the best.

If I'm going to cheat on my diet, I'll get the pecan pie.

[Narrator] Idahoans indeed love their sweets.

There's a choice to satisfy just about anyone's taste.

But only one area can claim to be the sweetest place in the state.

This is Sweet, Idaho, about ten miles northeast of Emmett.

[Kennie Lyn Klingback] Sweet is named for the brothers, Zeke and Vern Sweet.

They were the nephews of our first pioneer settler, Andy McQuade.

[Narrator] The city got its name because of a bureaucratic mix up.

[Kennie Lyn] The original post office was at the Marsh Arton ranch in Montour.

And you either had to swim the river or call for the boat to come and get you to go to the post office.

So the postal inspectors decided there was enough people in this valley to have their own post office.

They ask the brothers, Zeke and Vern to be the postmasters.

And Zeke said, We just have a cabin.

We just live in one room.

And the inspector said, All you need is a box under the bed.

So that was Sweet's first post office.

And the boys sent off the paperwork to Washington to be the Sweet Brothers' post office.

It came back as Sweet.

So that's how we got our name.

[Narrator] So where is the sweetest spot in Sweet, Idaho?

Klingback had a piece of advice.

Be careful picking the sweetest spot in Sweet, Idaho.

We have lots of good cooks here.

Make lots of good desserts.

{Narrator] So warned.

This is Sweets largest restaurant.

[Paul Anderson] Anderson Reserve started out as a goal of of being a butcher shop with a plan that maybe customers could taste our product before they bought it and left.

And so a little idea of having a restaurant developed and has drastically snowballed from just being a little idea We're a restaurant, butcher shop wine and whiskey bar.

There it is.

[Narrator] Chef Buck Namba crafts desserts by hand with attention to detail.

[Paul] Well the desserts that Chef Buck make are definitely sweet.

But if you want the sweetest treats and Sweet, Idaho, I got to introduce you to my mom Phemia's famous cinnamon rolls and sticky buns.

This is my mom, Phemia.

Hi.

I'm making cinnamon rolls this morning.

[Narrator] Phemia makes 24 rolls each day and a few extra sticky buns.

[Phemia] First, I start with adding my flour, sugar and the yeast, and then I put in my egg and lots of good butter.

That's what makes them so good.

And we just let it beat for about 2 minutes.

It will get all incorporated in there and then you kind of want your dough to be kind of sticky, but kind of not, because then it's too hard and you end up rolling more flour into it, which will make more of a tough cinnamon roll.

So you try to keep it on the sticky side.

[Narrator] Then let the dough raise for about an hour.

[Phemia] And so now you just kind of get your table prepared and then just kind of knock down your dough and and see how it's kind of on the sticky side, which is what you want.

And then we'll just kind of knead it.

Mostly the flour is to keep it from sticking to your table.

You don't want to knead a lot into the dough.

You just kind of get that feeling for it.

And then it should come out like that.

And then we'll be ready to roll it out.

So then once you get it rolled out and I usually put more butter on it, we like butter, so I put lots of butter.

I think that would helps give it a lot of its good flavor.

And then I already have some cinnamon sugar.

And at this point you just try to roll it as tight as you can, but it doesn't really matter.

And then .

.

.

we're just down to cutting it, and it's kind of sticky, so sometimes you have to flour your knife.

Well, now that they've had about an hour to raise, they have more than doubled in size.

So they're ready to go in the oven.

And I usually do 350 degrees for about 6 minutes.

Now we're ready to put the icing on it.

I like a butter cream icing, and it's made of the cream cheese butter, powdered sugar and vanilla and a little bit of milk.

I love doing this and I love the fact that I did it with my grandma.

That's what makes it the sweetest part for me.

And there isn't a day go by that I'm making these that I don't think of her.

I just hope that reflects in into what I'm making for someone else, that it might sweeten their day a little bit.

[Narrator} So that's the sweetest spot.

Not a place, but a memory.

Not just a thing, but something made with love.

And whether it's an historic candy bar, a box of your favorite chocolates, a cool ice cream cone, a piece of freshly baked pie, or a warm cinnamon roll.

Idaho offers plenty of sweet treats.

[Narrator] Idaho Experience is made possible with funding from the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, devoted to preserving the spirit of Idaho from Anne Voilleque and Louise Nelson from Judy and Steve Meyer with additional support from the J.A.

and Katherine Albertson Family Foundation, the Friends of Idaho Public Television, the Idaho Public Television Endowment and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S6 Ep5 | 1m 20s | Learns the secrets of Idaho’s iconic sweet-treat historic entrepreneurs. (1m 20s)

Preview: S6 Ep5 | 30s | Learns the secrets of Idaho’s iconic sweet-treat historic entrepreneurs. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer. Additional funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson...