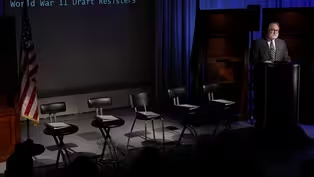

The Nisei Paradox: Japanese American World War II Draft Resisters | Full Performance

Clip: Season 8 Episode 1 | 59m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII.

In World War II, 44 Japanese American men at Minidoka resisted government conscription into the US military, refusing to be drafted by a country that considered them less than full citizens. Their case is being retold 80 years later by the Friends of Minidoka – and by a group of Idaho lawyers who wrote and produced a play.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer. Additional funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson...

The Nisei Paradox: Japanese American World War II Draft Resisters | Full Performance

Clip: Season 8 Episode 1 | 59m 3sVideo has Closed Captions

In World War II, 44 Japanese American men at Minidoka resisted government conscription into the US military, refusing to be drafted by a country that considered them less than full citizens. Their case is being retold 80 years later by the Friends of Minidoka – and by a group of Idaho lawyers who wrote and produced a play.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Idaho Experience

Idaho Experience is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship[Ronald E. Bush] It is my privilege to give to you under the creative and directing genius of Mr. Jeff Thompson, the performance of The Nisei Paradox.

Narrator: After the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, over 110,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast were relocated to internment camps in Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho.

Over 13,000 were relocated to the 33,000 acre Minidoka War Relocation Camp, also known as the Hunt Camp, making it the seventh largest city in Idaho.

Many were Nisei, second generation Japanese Americans born in the United States and therefore U.S. citizens.

On a per capita basis, more Nisei internees from the Minidoka Relocation Camp served in the armed forces than from any other relocation camp.

42 young men refused to serve.

This is their story.

Mary Smith: My neighbors are very polite, very hardworking, very respectful.

But I hear that they might be spies and saboteurs.

I'm.

I'm.

I'm worried for my children.

Mary Smith, mother of three.

Pres.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: Whereas the successful prosecution of the war requires every possible protection against espionage and against sabotage.

Now, therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in the President of the United States as Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy, the Secretary of War is hereby authorized and directed to prescribe military areas from which any or all persons may be excluded.

Executive Order Number 9066 signed Franklin D. Roosevelt, The White House, February 19th, 1942.

[Audio Alert] Announcer: By order of the United States Army, all Japanese must register with the local sheriff's office.

A curfew is hereby implemented, and all individuals of Japanese ancestry must remain in their homes between the hours of 8 p.m. and 6 a.m.. A travel ban is hereby implemented, restricting individuals of Japanese ancestry from traveling more than five miles from their residence.

[Audio Alert] Announcer: By order of the United States Army, all individuals of Japanese ancestry must immediately surrender to the local sheriff's office all flashlights, cameras, radios, firearms, and any other items that might be used as a weapon.

[Audio Alert] Announcer: By order of the United States Army, all persons of Japanese ancestry are to report for immediate evacuation from the West Coast Military Area.

Announcer: All Japanese Americans are urged to comply with all orders of the United States of America.

It is our patriotic duty to support our country.

Japanese-American Citizens League.

Federal Agent: Governor Clark, the federal government is simply asking that Idaho accept its fair share of West Coast Japanese Americans.

They will be placed in a reception center paid for by the U.S. Army.

At this reception center this pioneer community can be put in the fields, and we can harness their well known industriousness so they can help serve the war effort.

Gov.

Clark: As Governor of Idaho, I am opposed to bringing the Japanese into my state.

I want to admit right at the start that I am so prejudiced as to my reasoning.

Well, I might be a little off because I don't know which ones I can trust, so therefore I don't trust any of them.

But if you are insistent on bringing them into my state, here are my conditions.

First, they must be brought here under military supervision.

Second, they must be forbidden from buying land in Idaho.

I am unwilling to sell the state of Idaho to the Japanese for a few dollars, while our American boys are dying to prevent Japan from taking the state of Idaho by force of arms.

I don't want those who come after us to find recorded on the page of history that we sold our state to the Japanese while our soldiers were fighting to defend it.

Third, all Japanese Americans who are brought to the state must be forced to return to the West Coast at war's end.

And finally, most importantly, all Japanese sent to Idaho must be placed under guard and confined in concentration camps for the safety of our people, our state, and the Japanese themselves.

Washington State Police Chief: A Jap is a Jap, whether a citizen or not.

Chief of Police.

Washington State.

[Audio Alert] Announcer: All males of Japanese ancestry are classified 4C, enemy alien, and cannot serve in any capacity in any of the United States Armed Forces.

U.S. Army Sgt.

: You can't trust a Jap to fight in the South Pacific.

Hell, you can't trust a Jap to fight at all.

Sergeant.

United States Army.

[Audio Alert] Announcer: Any male of Japanese ancestry who is physically fit and mentally sound may volunteer to serve in the armed forces.

War Dept.

Spokesman: There is a shortage of soldiers, and the need for manpower has never been greater.

War Department Spokesman.

[Audio Alert] Announcer: All males of Japanese ancestry are hereby reclassified as 1A, and must report to duty upon receipt of an induction notice.

We in the American Armed Forces are happy to welcome you Japanese among our ranks.

Even though your country, Japan, is at war with the United States.

The fact that you, young Japanese, are willing to fight against your country should prove to all that there are a few Japanese who are good Americans.

I congratulate you, Japanese, for making a splendid record in our army, where you are welcomed and given all of the rights and privileges of any other citizen who was brought into the service.

Lieutenant, B.N.

Herrington: Army Traveling Induction Board.

Minidoka Relocation Camp, Swearing and Induction Ceremony, 1944.

George Takei: And I went to school, you know, behind those barbed wire fences.

And we started every, began every morning with the pledge of allegiance to the flag.

I mean, I could see the barbed wire fence and the sentry towers and the machine gun right outside my schoolhouse window as I recited the words “with liberty and justice for all.” Gene Akutsu: The United States has always been my country.

If the government wants me to serve and possibly sacrifice my life, they should return my citizenship, my rights and liberty.

It is wrong to rob me of my rights, and then to use me to fight to defend those rights for others.

Gene Akutsu, Minidoka Relocation Camp.

Pres.

Franklin D. Roosevelt: No loyal citizen of the United States should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry.

The principle on which this country was founded, and by which it has always been governed, is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart.

Americanism is not and never was, a matter of race or ancestry.

President Franklin D Roosevelt, Creating the Japanese American 442nd Infantry Regimental Combat Team, February 1, 1943.

Bailiff: Hear ye, hear ye, hear ye.

On this 13th day of September, in the year of 1944, and in the matter of the Japanese American draft evaders Idaho Federal District Court Judge Chase A. Clark presiding.

All persons with business before this honorable court will now be heard.

Judge Clark: Gentlemen, thank you for accepting my invitation to be here today.

Each of you is known to me to be the best and most capable attorneys in Boise.

I see Carl Burke, Jess Hawley, Fred Taylor, Mr. Everly, Willis Moffett, Vernon Kay Smith, French Alphont.

Loren Elam good to see you.

As you know, there's no right to counsel guaranteed to a criminal defendant, even if unable to afford one.

But I have 33 Japanese individuals who have been indicted for violating the Selective Training and Service Act who need representation.

All trials will be held this week and next and will be conducted on Saturday.

I hereby exercise my inherent power and appoint each of you to represent one or more of these individuals.

None of you will receive compensation for your services.

Let's just chalk it up to your civic duty to the State of Idaho and the United States Government, and your contribution to the war effort.

Bailiff: Hear ye, hear ye, hear ye.

All rise.

Calling United States versus James Mitsugu Yamada.

This is a time and place for the trial of James Yamada, charged with violating the Selective Training and Service Act.

Federal District Court Judge Chase A. Clark presiding.

Judge Clark: Please be seated.

Who appears for the United States?

Jonathan Blake: I do, Your Honor.

Jonathan Blake.

And who appears for the defendant?

Let me see.

Who is today’s defendant?

Ah, Mr. Yamada.

Matthew Kane: Matthew Kane for the defendant, your honor.

If it please the court, I have a preliminary matter.

I would like to renew my objection to being forced to be here today.

As I have previously noted, given my personal feelings toward the Japanese, I do not feel I can adequately represent Mr. Yamada.

Judge Clark: It does not please the court.

And as I have previously explained to you, Mr. Kane, it is your civic duty as a lawyer to appear before this court when called to do so, no matter how distasteful the matter may be.

I have 33 cases currently pending before me and two weeks to try them all.

I have too few lawyers as it is.

Please do not resist this particular call to arms, Mr. Kane, and be an example of how to act when called to serve.

Your objection is again overruled.

Mr. Kane: Very well, Your Honor.

I request that you recuse yourself from these proceedings.

Judge Clark: I sincerely hope, Mr. Kane, that your request is not in retaliation to my kind invitation for you to join us here today.

Mr. Kane: Not at all, Your Honor, but as you say, I have a civic duty to appear and defend my client.

I will do my best.

I would be remiss in my civic duty, however, if I did not point out to the court that the federal law requires disqualification of a judge who has a personal bias or prejudice by reason of which the judge is unable to exercise his functions in a particular case, in a fair and impartial manner.

Judge Clark: What is the basis for your request that I recuse myself?

Mr. Kane: your honor, in 1942, when you were Governor of Idaho, you made some rather inflammatory statements about Japanese Americans and the government's effort to bring them to Idaho.

You were also heavily involved, if not one of the architects of the very internment camp in which Mr. Yamada has been incarcerated.

And it is because of that incarceration, along with other injustices, that he has resisted the draft.

The very constitutionality of these proceedings, because of Mr. Yamada’s incarceration in the Minidoka camp will be a centerpiece of his defense.

I do not believe you can sit impartially on a matter.

Your actions as governor, in part created.

Judge Clark: Mr. Kane I am the only federal district court judge in the state of Idaho.

There are no other choices.

Many of these individuals, including your client, have been waiting in the Ada County Jail for five months for their trials.

If I recuse myself, these individuals, including your client, might wait in jail for another five months or more before a judge from some other state is brought in.

I think it's time for these individuals, including your client, to have their day in court.

Like you, Mr. Kane, I can put aside my personal feelings and proceed in a fair and impartial manner despite my personal feelings.

Your request for my recusal is denied.

You may sit.

Mr. Kane.

Any preliminary matters, Mr. Blake?

Mr. Kane: I'm sorry, Your Honor.

I have one more civic duty to perform.

My client takes exception to the indictment and asks that it be quashed.

Judge Clark: On what grounds, Mr. Kane?

Mr. Kane: The indictment should be quashed because it violates the time honored doctrine of due process.

Due process cannot give way to overzealousness.

in an attempt to punish via the criminal process those who we may regard as undesirable citizens.

How is due process served when an American citizen can be confined on the ground of disloyalty and then, while under duress and restraint, be compelled to serve in the armed forces of the very country that has so confined him?

And then be prosecuted for not yielding to such compulsion?

The Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause forbids the federal government from taking away a person's liberty without due process of law.

The arrest and prosecution of Mr. Yamada violates those due process rights.

Judge Clark: Mr. Kane, I have provided a presided over many of these cases, and the evidence in each of these cases shows that numerous procedural safeguards were in place.

The Selective Training and Service Act puts individuals eligible for the draft on clear notice that resisting the draft is illegal.

Each defendant was provided with a draft notice.

Each defendant was given an opportunity to appear before his local draft board.

If he failed to do so, a warrant for his arrest was issued.

Each defendant was provided an opportunity to post bail.

I have given each defendant an attorney and each defendant has been given a jury trial.

I'm sure that the evidence will show that your client was given the same procedural safeguards.

To the extent your argument is based on some nebulous, substantive due process right.

I would point to the fact that nearly every other similarly situated individual in the Minidoka Relocation Center complied with their draft notice, and did not appear to suffer a deprivation of any legally recognized liberty right.

Mr. Kane: There is one factor that distinguishes Mr. Yamada from so-called similarly situated individuals.

Mr. Yamada has given up his U.S. citizenship because we have treated him as a non-citizen.

Because Mr. Yamada is no longer a United States citizen, the Selective Training and Service Service Act does not apply to him.

Judge Clark: Now, let me stop you right there, Mr. Kane.

When did Mr. Yamada give up his citizenship?

Before or after he was ordered to report for the service?

Mr. Yamada?

Mr. Yamada: After.

Judge Clark: All right, then.

You can't change your citizenship at the snap of a finger.

You especially can't do so after you've violated the law of the land in which you previously claimed citizenship.

A change of masters after the fact cannot excuse the crime before.

The motion to quash the indictment is denied.

Mr. bailiff, please bring in the jury.

Narrator: The jury pool from which the juries were selected consisted of 34 white, mostly male Idaho citizens.

The same jury pool was used in all trials held in 1944.

Mr. Kane One more preliminary matter, Your Honor, before the jury enters.

Judge Clark: Mr. Kane, your definition of civic duty has far outstripped mine.

And the exercise of your definition of civic duty is exhausting the patience of this court.

Make it quick.

Mr. Kane: Thank you, Your Honor.

I challenge the entire jury.

I have observed several of the prior draft resister trials, and I would note for the record, that many of the jurors sitting on my client's jury were also jurors in those prior trials.

nearly all of those jurors have returned the guilty verdicts, and I feel that they may not be free of bias.

I am not challenging the jury based on racial prejudice.

Excusing any individual involved in these trials based on that prejudice has already been denied by the court.

You denied my request to be excused as counsel.

You denied my request that you recuse yourself as judge.

I don't intend to ask to excuse any jurors on the basis of racial prejudice.

Instead, I challenge the jury because they have heard evidence in other cases and found other defendants guilty.

I fear that they have already made up their minds regarding the guilt of my client before them the evidence and arguments have been presented in this matter.

Judge Clark: Mr. Kane, during voir dire, I asked each of the jurors if they could set aside their prejudices and biases and be fair in their deliberations.

I believe that would encompass all prejudices and biases, including any that may have been formed by sitting on other trials.

They each responded that they would.

Now, Mr. Kane, are you challenging the honesty of these good citizens?

Mr. Kane: Your Honor, my personal observation show that their actions speak louder than their words.

Upon conclusion of the trial, immediately before this one.

The jurors did not return to the jury room to deliberate.

Instead, they retired to the hallway to have a smoke.

And in less than five minutes, return to find the prior defendant guilty without any deliberations at all.

Several of those jurors sit on Mr. Yamada's jury.

Judge Clark: Mr. Kane, I understand your concerns, but I believe I can assuage them.

I will instruct the jury that they must return to the jury room to deliberate.

And if they desire to smoke their cigarettes, do so there.

I will also instruct the jury that they must base their verdict on the evidence presented in this trial only, and cannot take into the jury room any preconceptions based on any extraneous matters.

Now, Mr. Kane, it is my deep desire that you will allow me to bring in the jury and begin this trial.

Any objections?

Mr. Kane: No, Your honor.

Judge Clark: The jury is seated.

Mr. Blake, please proceed.

Mr. Blake: Thank you, Your Honor.

I call Josiah Montgomery to the stand.

Mr. Montgomery, you understand you were under oath.

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: What is your occupation?

Mr. Montgomery: I'm a special agent with the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Mr. Blake: Mr. Montgomery, in front of you is plaintiff's exhibit number one.

What is it?

Mr. Montgomery: It is a draft registration certificate for one James Mitsugu Yamada.

Mr. Blake: Mr. Yamada was duly registered for the draft?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: What was Mr. Yamada’s classification?

Mr. Montgomery: 1A.

Mr. Blake: What does that mean?

Mr. Montgomery: That he was eligible for the draft.

Mr. Blake: Was the defendant, Mr. Yamada, called to report for induction?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: How is that done?

Mr. Montgomery: A notice is sent from the local draft board to the last known address of the individual.

Mr. Blake: was a draft notice sent to Mr. Yamada?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: How do you know that?

Mr. Montgomery: I have a copy of his draft notice here.

It's plaintiff's exhibit number two.

Mr. Blake: Did the defendant receive his draft notice?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: How do you know that?

Mr. Montgomery: I received Plaintiff’s exhibit two for Mr. Yamada.

Mr. Blake: Did the defendant report to the local draft board?

Mr. Montgomery: No, he did not.

Mr. Blake: And how do you know that?

Mr. Montgomery: I received a letter from the Jerome County Draft Board informing me that Mr. Yamada had failed to report.

That's plaintiff's exhibit number three.

Mr. Blake: What happened then?

Mr. Montgomery: A warrant was issued and I had him arrested.

Mr. Blake: On what grounds?

Mr. Montgomery: For violating the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, when he failed to report for induction into the armed forces of the United States of America.

Mr. Blake: What did you do when you had the defendant arrested?

Mr. Montgomery: I asked him if he was the person identified on the registration card.

He said he was.

I asked if he received a draft notice.

He said he did and gave me the notice, which is exhibit two.

I provided him with a copy of his Selective Service questionnaire, read to him questions 27 and 28, and I asked him to confirm his responses.

Mr. Blake: Mr. Montgomery, please explain to the jury what the Selective Service questionnaire is.

Mr. Montgomery: This is a questionnaire that is required to be filled out by all Japanese Americans who resided in the West Coast Military Area.

Mr. Blake: Is that plaintiff's exhibit number four?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: Is this commonly known as the loyalty oath?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes it is.

Mr. Blake: And what do questions 27 and 28 ask?

Mr. Montgomery: Question 27 asks, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?” Question 28 asks, “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any and all attack from foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor or any other government power or organization?” Mr. Blake: Did Mr. Yamada respond?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: What were his responses?

Mr. Montgomery: He responded no to both.

He was a no-no boy.

Mr. Blake: A what?

Mr. Montgomery: A no-no boy.

A person who answered no to both questions.

Mr. Blake: Let me make sure I understand.

Are you telling this jury that Mr. Yamada refused to serve this country and refused to renounce his allegiance to the Japanese Emperor?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: Did Mr. Yamada make any other statements?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

He sent a letter to the Jerome County Draft Board.

I have it here.

Plaintiff’s exhibit number five.

He said, “I'll stick to Japan and you can have my U.S. citizenship papers.

It's never done me any good since I have a dual citizenship.

I'll keep the Japanese citizenship any day to the U.S.’s.

Mr. Blake: Upon his arrest, did Mr. Yamada retract his responses to the loyalty oath or his statements made to the Jerome County Draft Board?

Mr. Montgomery: No, he did not.

Mr. Blake: What happened after you arrested Mr. Yamada?

Mr. Montgomery: He was transported to the Ada county jail.

Mr. Blake: Thank you, sir.

I have no further questions.

Judge Clark: Do you have any questions of Special Agent Montgomery, Mr. Kane?

Mr. Kane: Yes.

Mr. Montgomery, where did you arrest my client, Mr. Yamada?

Mr. Montgomery: In Hunt, Idaho, in Jerome County.

Mr. Kane: No.

Mr. Montgomery, where exactly did you arrest my client?

Mr. Montgomery: At the reception center for Japanese Americans who have been relocated from the West Coast military area located at Hunt, Idaho Mr. Kane: Reception center?

Did you say reception center?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: I see.

Is this reception center enclosed by a barbed wire fence, Mr. Montgomery?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: Are there watchtowers located on the perimeter of this barbed wire fence?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: Are there military personnel stationed at this reception center?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: And do they have guns, Mr. Montgomery?

Mr. Montgomery: Uh, yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: Are the individuals who reside there allowed to move freely into and out of this reception center.

Mr. Montgomery: Not that I'm I'm aware of.

Mr. Kane: Now, where in this reception center was my client when you arrested him?

Mr. Montgomery: In one of the barracks.

Mr. Kane: You had a warrant for his arrest?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: And did you arrest my client in private?

Mr. Montgomery: Uh, private, sir?

Mr. Kane: When you arrested him, was there anyone else present?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

There was me and two military policemen.

His mother and father were there, along with, I believe, two sisters.

Mr. Kane: Anyone else?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes.

Well, all the other families who lived in the barracks.

Mr. Kane: Did my client resist?

Mr. Montgomery: No, sir.

Mr. Kane: Did you take him from the barracks and out of the gate under guard?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: And you said you took him to the Ada County Jail.

How long of a drive is that?

Mr. Montgomery: Three, three and a half hours.

Mr. Kane: Have you been involved in other arrests at the Minidoka Reception Center?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: And these other arrests were of draft resisters?

Mr. Montgomery: Uh, no, sir.

We arrested draft evaders.

Mr. Kane: How many draft resisters, Mr. Montgomery?

Mr. Montgomery: Uh, I have been involved in the arrest of over 30 Japanese American draft evaders.

Mr. Kane: All of these draft resisters were located at the Minidoka Reception Center.

Mr. Montgomery: Uh, the relocation camp.

Uh, yes, sir.

Mr. Kane: Mr. Montgomery, you mentioned that Mr. Yamada was classified 1A, and that made him eligible for the draft.

Do you know what his classification was before?

Mr. Montgomery: I believe it was 4C.

Mr. Kane: What does that mean?

Mr. Montgomery: It means he was classified as an enemy alien and was not qualified to serve in the armed forces.

Mr. Kane: And do you know why his classification changed from enemy alien?

Mr. Montgomery: As I understand it, we needed more bodies to fight the war.

Mr. Kane: Fight whom?

Mr. Montgomery: The Germans.

Mr. Kane: Why do you say the Germans?

Mr. Montgomery: Well, you couldn’t very well expect the Japs, I mean, the Japanese living in this country to fight their own kind.

Mr. Kane: Mr. Montgomery.

Are there any Germans incarcerated at the Minidoka Reception Center?

Mr. Montgomery: Not that I'm aware of.

Mr. Kane: How about Italians?

Mr. Montgomery: No, sir.

Mr. Kane: I have no further questions.

Judge Clark: Any redirect, Mr. Blake?

Mr. Blake: Mr. Montgomery, did Mr. Yamada report for duty to the Jerome County Draft Board?

Mr. Montgomery: No, sir.

Mr. Blake: If an individual of German descent had failed to report for duty, would you have arrested him?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: Have you arrested any non-Japanese Americans for draft evasion?

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

I have arrested several Caucasians, mostly Jehovah's Witnesses.

Mr. Blake: Then it doesn't matter what background a person has.

If they evade the draft, they are arrested.

Mr. Montgomery: Yes, sir.

Mr. Blake: I have no further questions.

Mr. Kane: One more question, Mr. Montgomery.

Are these Jehovah's Witnesses incarcerated behind barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers?

Mr. Montgomery: Of course not.

Judge Clark: Special Agent Montgomery, thank you for your testimony today.

You're excused.

Mr. Blake, any more witnesses?

Mr. Blake: No, Your Honor.

United States rests.

Judge Clark: Mr. Kane, you may call your first witness.

Mr. Kane: Your Honor, I would like to call to the stand James Yamada.

Mr. Yamada, where do you currently reside?

Mr. Yamada: The Ada County Jail here in Boise.

Mr. Kane: How long have you resided there?

Mr. Yamada: About five months.

Mr. Kane: Prior to residing in the Ada County Jail where did you reside?

Mr. Yamada: In the Minidoka Concentration Camp.

Mr. Blake: Objection, Your Honor.

Judge Clark: Sustained.

Mr. Yamada, you will refrain from using pejorative words.

The federal installation located near Hunt, Idaho, is called the Minidoka Relocation Center.

Please refer to it as such.

Mr. Kane: Mr. Yamada, does it feel like a relocation center to you?

Mr. Yamada: No.

Mr. Kane: Why not?

Mr. Yamada: Well, I have been relocated there, but it feels more like a P.O.W.

camp.

Mr. Kane: Why a P.O.W.

camp?

Mr. Yamada: I feel like me and my family are prisoners of war.

A war broke out.

We were taken prisoners.

So if it's not a concen.

.

.

If it's not the other type of camp, it's at least a P.O.W.

camp.

Mr. Kane: Is there any difference between your current and prior living conditions?

Mr. Yamada: Not really.

At the jail, there's barbed wire around the exercise yard.

There are guard towers.

There are guards with guns.

And I'm not free to leave when I want.

The only difference is that my family is not in jail with me.

Mr. Kane: How did you come to be at Hunt?

Mr. Yamada: My family and I were forced to leave our home in Seattle and taken to a holding pen.

I remember we were given a tag to wear.

It had a number on it.

No name, just a number.

About six months later, we were shipped by train to the camp.

Mr. Kane: Were you allowed to bring anything with you?

Mr. Yamada: We were each allowed to bring one suitcase.

That was all.

Mr. Kane: What happened to the rest of your belongings?

Mr. Yamada: We had to leave them.

Our neighbors helped themselves.

Those neighbors who were not Japanese.

Mr. Kane: What happened to your home?

Mr. Yamada: Sold it.

My father told me it sold for less than half of what he paid 20 years ago.

Sold it to one of our neighbors.

One of our neighbors who is not Japanese.

Mr. Kane: Tell me about the Minidoka Reception Center.

Mr. Yamada: I like that.

Reception Center.

Wasn't much of a reception.

We were taken from the train station to the camp, under guard by soldiers.

There were as many of them, as there were of us.

We were told the guards there were for our protection, but they all faced in looking at us.

They weren’t looking out at the spectators.

They said the same about the camp.

It was there to protect us.

But the guards watched us, not the people outside the camp.

When we got there, the barbed wire was up and some of the barracks looked like they were finished, but a lot of them were still being built.

They put us in one that had about 20 people.

The roof wasn't finished yet.

The walls had tar paper on them.

It was always windy and cold or windy and hot or windy and dusty.

There was no running water.

We had one outhouse.

Mr. Kane: Did you receive a draft notice?

Mr. Yamada: Yes.

Mr. Kane: Did that surprise you?

Mr. Yamada: Yes and no.

I mean, I was required to register for the draft, but I didn't think they would actually draft me.

Mr. Kane: Why not?

Mr. Yamada: Because before, all of us were classified as enemy aliens and we were told we couldn't serve in the military.

We were classified as the enemy.

Just like the Nazis.

Can you imagine drafting a Nazi to fight for the United States?

I couldn't, so if they weren't going to draft Nazis because they were the enemy, I couldn't imagine they would draft us after declaring us enemy aliens unfit to serve.

We thought we were no longer U.S. citizens.

Especially after they threw us in these camps.

Then they changed the rules and classified us as 1A.

Suddenly we're all qualified to serve our country.

It seemed a little inconsistent.

Mr. Kane: Take a look at plaintiff's exhibit number four.

Did you fill out a Selective Service questionnaire, the loyalty oath?

Mr. Yamada: Yes.

Even though no one else had to.

Mr. Kane: What do you mean?

Mr. Yamada: Only Japanese Americans were required to fill out this loyalty oath.

I don't know why we had to when no one else did.

German Americans didn't have to.

Italian Americans didn't have to.

Just imagine requiring Joe DiMaggio to sign a loyalty oath.

Mr. Kane: Take a look at question 28.

What did you answer to the following question?

“Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack from foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese Emperor or any other foreign government power or organization?” Mr. Yamada: I answered, “No.” Mr. Kane: Why, “No?” Mr. Yamada: Because the question assumed that I was loyal to Japan and obeyed the Emperor.

I wasn't born in Japan.

I was born here.

I never lived in Japan.

I have always lived here.

This was my country.

I have never been loyal to Japan.

I never obeyed the Japanese Emperor.

The question felt like a trap.

Why should I have to renounce something that I never felt in the first place?

Mr. Kane: Take a look at question 27.

It asks, “Are are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?” How did you respond?

Mr. Yamada: “No.” Mr. Kane: Why did you answer, “No?” Mr. Yamada: How could I pledge to serve in the army of a country that treated me like I was the enemy, and put me and my family behind barbed wire?

Mr. Kane: Is that why you did not appear before the draft board?

Mr. Yamada: That and other reasons.

Mr. Kane: What other reasons?

Mr. Yamada: If I suddenly became loyal enough to be drafted to fight for the United States, I should be loyal enough to be released from that camp.

Why should I fight for a country that, while I'm fighting that same country, is holding my family hostage?

Why should I fight for freedoms that have been taken away from me and my family?

Mr. Kane: Why have you given up your U.S. citizenship?

Mr. Yamada: I hadn't given it up.

It was taken away from me.

All they have left me is my ancestry.

My race.

If that's all I have, then I better take it or I'll have nothing.

Otherwise, I'll be a man without a country.

Mr. Kane: Are there any circumstances under which you would serve?

Mr. Yamada: Yes.

If they would treat me like an American citizen, I would accept my duties as an American citizen.

If they would release my family.

I would gladly serve.

But instead they tell me I have no choice.

And I must fight for a country that doesn't fight for me or my family.

Mr. Kane: Thank you, Mr. Yamada.

I have no further questions, Judge Clark: Mr. Blake, any questions?

Mr. Blake: Mr. Yamada, Do you understand the concept behind the draft?

Mr. Yamada: Yes.

Mr. Blake: Well, I'm not sure you do.

You testified that you are being forced against your will to serve in the armed forces of this country.

But then you testify that if you had your freedom, you would be willing to serve.

Do you see the contradiction in that?

Mr. Yamada: No.

Mr. Blake: Mr. Yamada, the draft is not voluntary.

No individual called to serve has a choice.

He is required to serve.

He must serve.

No individual is allowed to say that his particular circumstances or allow him to say no.

That's true whether that person is German, Italian, Irish, American or Japanese.

Do you understand that every United States citizen eligible for the draft who fails to report to the draft board, is subject to prosecution for violating the law?

Mr. Yamada: Yes, I understand that.

Mr. Blake: Then what makes you different from everyone else?

Mr. Yamada: I do not have the rights of a U.S. citizen.

Why should I have to accept the duties of one?

Mr. Blake: Mr. Yamada, did other Japanese American men who were relocated to the Minidoka camp answered the call to serve in the U.S. Armed forces?

Mr. Yamada: Yes.

Mr. Blake: Most of them did.

Isn't that right?

Mr. Yamada: A lot did.

Mr. Blake: But you didn't.

Did you?

Mr. Yamada: No.

But you know what?

When they were given furloughs to see their families, their wives or their girlfriends, they had to come back to the camp.

They were locked in again behind barbed wires, and they were guarded by their fellow soldiers.

They may be serving their country, but their country still treats them like the enemy.

Mr. Blake: Move to strike, Your Honor.

Judge Clark: Granted.

Gentlemen of the jury, you're instructed to ignore Mr. Yamada’s last remarks.

Mr. Blake, any further questions?

Mr. Blake: No, Your Honor.

Mr. Kane, any other questions?

Mr. Kane: No.

Your honor.

Judge Clark: Mr. Yamada, you may step down.

Mr. Kane, any other witnesses?

Mr. Kane: No, Your Honor.

The defense rests.

Judge Clark: We will recess and reconvene in 30 minutes for closing arguments.

Gentlemen, please proceed with your closing arguments.

Mr. Blake, you are first.

Mr. Blake: Thank you, Your Honor.

May it please the court, counsel.

Gentlemen of the jury, the only matter to decide today is whether James Mitsugu Yamada violated the Selective Training and Service Act.

That act makes it a crime for a male citizen of the United States of America to unlawfully, knowingly, willfully, and feloniously evade the draft by failing to report for induction into the armed forces.

The question is, the only question is, did Mr. Yamada knowingly and willfully fail to report for induction?

You've heard the evidence.

Special Agent Montgomery testified that Mr. Yamada did not appear at the Jerome County Draft Board.

Mr. Yamada admitted That he didn't.

He admitted he failed to report for duty.

Now, you also heard Mr. Yamada give you reasons why he didn't report.

But these reasons only prove that he knowingly and willfully did not report for duty.

If a person has reasons for not doing something, he knows it's something that should have been done but willfully chose not to do it.

But more importantly, those reasons for not appearing do not excuse his crime.

They are not relevant to today's proceedings.

The United States is not on trial here.

President Roosevelt's executive order is not on trial here.

The relocation of Japanese Americans out of the West Coast Military Area is not on trial here.

The treatment of Japanese- Americans is not on trial here.

Only Mr. Yamada is on trial here today.

The reasons Mr. Yamada gave for not reporting for duty are not exceptions to the law.

They do not excuse his conduct.

In relation to the Selective Training and Service Act.

Mr. Yamada is being treated the same as any other citizen of these United States.

If I failed to report for the draft, I would be sitting where Mr. Yamada is sitting, and I would be as guilty as he is.

Mr. Yamada failed to report for duty.

That is a crime.

No matter what his excuses are, he's guilty of that charge.

Judge Clark: Thank you, Mr. Blake.

Mr. Kane, your closing argument.

Mr. Kane: Mr. Blake, is correct.

If he was eligible for the draft and he failed to appear, he would be subject to prosecution.

But he can only be found guilty if he broke the law.

Here the law, the Selective Training and Service Act does not apply to Mr. Yamada.

Mr. Blake correctly set forth the elements of that law and to whom that law applies.

And as Mr. Blake said, the law is broken.

If a male citizen of the United States, fails to report for duty.

Mr. Yamada did not break that law because Mr. Yamada was not a citizen of the United States of America.

How could he be?

He was classified as an enemy.

He was forced from his home, put in a holding pen, and transported hundreds of miles to the sagebrush desert of south central Idaho.

Mr. Yamada was incarcerated behind barbed wire and was deprived of his freedom, of his liberty.

All of this was done without warrant.

All of this was done without a hearing.

All of this was done without a trial.

All of this was done without a hint of due process.

At no time did Mr. Yamada have the ability to challenge his incarceration.

This is not the way of the United States of America.

Mr. Yamada has been stripped of his United States citizenship.

But Mr. Blake says, “He broke the law because he didn't fulfill his duties as a citizen.” Mr.. Yamada stands before you, not as a citizen of the United States of America, but as a man who has been classified as an enemy alien, a man without the liberties guaranteed to the citizens under the United States Constitution.

A Selective Training and Service Act applies only to male citizens of the United States of America.

The prosecutor has put before you no evidence that Mr. Yamada was a citizen of the United States of America when he was told to report for duty.

The evidence put before you today proves he was not.

Because I think we can all agree that a citizen of the United States would not be treated the way Mr. Yamada has been treated.

Mr. Yamada was not a citizen subject to the Selective Training and Service Act.

But even if the law applied to Mr. Yamada, the law must be applied fairly.

Even Mr. Blake would have to agree that if he were in Mr. Yamada’s place, he would hope to be treated fairly.

How is it fair to require Mr. Yamada to fight for a country that has thrown him and his family into a camp surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by the military?

But Mr. Blake argues that the law is fair because my client is being treated the same as anyone else who fails to report for duty.

Mr. Blake says that if he failed to report, he would be in the same place as my client.

Mr. Blake has never been in the same place as my client.

Others who have resisted the draft, whether German American, Italian American, Jehovah's Witnesses have never been in the same place as my client.

None of them were taken from their homes, forced to sell belongings, placed behind barbed wire, and told by his country, that because of his ancestry, he was disloyal and an enemy.

That's why the law is unfair.

How is it fair to force Mr. Yamada to fight for freedoms neither he nor his family enjoy?

Finding Mr. Yamada guilty of resisting the draft of a country that has treated him as an enemy is in the purest sense, unfair.

Please do the right thing.

Do the fair thing and find Mr. Yamada not guilty.

Judge Clark: Thank you, Mr. Kane.

Gentlemen of the jury, it is your duty now to deliberate in this matter.

You will retire to the jury room to do so.

You must also apply the facts as presented to you in this trial only.

And apply those facts to the law.

Now, in applying the law, you are instructed that you are not to concern yourselves with how the defendant was treated by our government, by the military, or by anyone else.

Your soul duty today is to determine whether the defendant did or did not report for induction as ordered.

When you have reached your verdict, please advise the bailiff and he will escort you back to this courtroom.

Has the jury reached a verdict?

Jury Foreman: We have, Your Honor.

Judge Clark: And what is that verdict?

Jury Foreman: We, the jury, find James Matsugu Yamada guilty.

Judge Clark: Mr. Yamada, please approach the bench.

You've been found guilty of violating the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 by a jury of your peers.

It is my discretion what sentence to impose?

The maximum sentence is five years and a $10,000 fine.

You’re hereby sentenced to three years and three months to be served at the Federal Penitentiary at McNeil Island, Washington.

You're also fined $200.

Narrator: Of the 42 Japanese Americans from the Minidoka Relocation Camp who were indicted from September 1944 through February 1945, four pled guilty, 35 were found guilty, two were dismissed, and one was acquitted.

The acquittal, obtained by attorney Laurel Elam, was not based on a deprivation of a constitutional right or any concept of fairness, but rather on the basis that the evidence showed the defendant had not been sufficiently notified to report for induction.

This defendant was later retried and found guilty.

The four draft resisters who pled guilty were sentenced to 18 months.

Those who stood for trial were sentenced to between 3 and 3 and a half years.

At first, the convictions and sentences seemed anti-climatic for many of the draft resisters.

It had made little difference to them whether they were incarcerated in Minidoka or the Ada County Jail, or a federal prison.

But as it turned out, there was a difference.

On December 18, 1944, the U.S. Supreme Court held it illegal to detain American citizens of Japanese ancestry in internment camps.

On January 2nd, 1945, the military reopened the West Coast to Japanese Americans and those of Japanese ancestry.

Japan surrendered on September 2nd, 1945.

The Minidoka Relocation Camp was closed on October 28th, 1945.

But most of the Minidoka draft resisters remained incarcerated for another 18 months until April 1947, when they were paroled.

Justice Black: It should be noted to begin with that all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect.

Pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions.

Racial antagonism never can.

However, Korematsu was not excluded from the West Coast military area because of hostility to him or his race.

He was excluded because this country was at war with Japan, because of the fear of invasion, and because of the military judgment that was necessary to temporarily segregate Japanese-Americans from the West Coast.

Majority opinion.

Korematsu versus the United States.

Justice Murphy: This exclusion of all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien, from the Pacific Coast area, goes over the very brink of constitutional power and falls into the ugly abyss of racism.

The exclusion of these individuals is one of the most sweeping and complete deprivations of constitutional rights in the history of this nation in the absence of martial law.

Justice Murphy, dissent.

Korematsu versus United States.

Pres.

Harry Truman: As of this day, December 23rd, 1947, all Nisei draft resisters are hereby pardoned with restoration of all civil and political rights.

President Harry S. Truman.

Announcer: February 19th is the anniversary of a sad day in American history.

It was on that date, in 1942, in the midst of the response to the hostilities that began on December 7, 1941, that Executive Order Number 9066 was issued, resulting in the uprooting of loyal Americans.

Over 100,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were removed from their homes, detained in special camps, and eventually relocated.

We now know what we should have known then.

Not only was the evacuation wrong, but Japanese Americans were and are loyal Americans.

Now, therefore, Gerald R. Ford, President of the United States of America, calls upon the American people to affirm this American promise, that we have learned from the tragedy of that long ago experience forever to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American, and resolve that this kind of action shall never again be repeated.

Proclamation number 4417 An American Promise, February 19, 1976.

Announcer: Executive Order 9066 was not justified by military necessity and the decisions that followed it, the tension ending detention and ending exclusion were not driven by analysis of military conditions.

The broad historical causes which shaped these decisions were race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.

As a result, a grave injustice was done to American citizens and resident aliens of Japanese ancestry who, without individual review or any probative evidence against them, were excluded, removed and detained by the United States during World War II.

Report of the Congressional Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians.

Issued 1983.

Pres.

Ronald Reagan: My fellow Americans, we gather here today to write a grave wrong.

More than 40 years ago, shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living in the United States were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in makeshift internment camps.

This action was taken without trial, without jury.

It was based solely on race.

For these, 120,000 were Americans of Japanese descent.

Yes, the nation was then at war, struggling for its survival.

And it's not for us today to pass judgment upon those who may have made mistakes while engaged in that great struggle.

Yet we must recognize that the internment of Japanese Americans was just that, a mistake.

For throughout the war, Japanese Americans in the tens of thousands remained utterly loyal to the United States.

Indeed, scores of Japanese Americans volunteered for our armed forces, many stepping forward in the internment camps themselves.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team, made up entirely of Japanese Americans, served with immense distinction to defend this nation, their nation.

Yet back at home, the soldiers’ families were being denied the very freedom for which so many of the soldiers themselves were laying down their lives.

Congressman Norman Minetta, with us today, was ten years old when his family was interned.

In the congressman's words, “My own family was sent first to Santa Anita racetrack.

We showered in the horse paddocks.

Some families lived in converted stables, others in hastily thrown together barracks.

We were then moved to Heart Mountain, Wyoming, where our entire family lived in one small room of a roof tar paper barrack.” Like so many tens of thousands of others, the members of the Minetta Family lived in those conditions, not for a matter of weeks or months, but for three long years.

The legislation that I am about to sign provides for a restitution payment to each of the 60,000 survivors.

Japanese surviving Japanese Americans of the 120,000 who were relocated or detained.

Yet no payment can make up for those lost years.

So what is most important in this bill has less to do with property than with honor.

For here we admit a wrong.

Here we reaffirm our commitment as a nation to equal justice under the law.

Fred Korematsu: Having my conviction cleared, I am very happy.

But there is a lot more to be done yet.

And I would like that this never happens again to any American citizen, just because he looks a lot different from others.

If we go to war with some country, and a person looks like someone from that country and is put in prison for that, I know that's wrong.

Fred Korematsu, Gene Akutsu: When you feel that you are right, you should speak up because if it could happen to you, it could happen to anybody.

As long as you're a minority.

They can pick on you and they can incarcerate you as they did us, because you're a minority.

But if you get out there and speak out and speak out loud, I think, you will be able to combat those type of things.

As you notice that, the Jewish people, they stress the Holocaust year after year after year, until people are sick and tired of listening to that.

But what they're doing is to telling the people, don't forget.

Don't forget that this could happen to you.

The Holocaust.

And in the same manner, we should go out there and tell the people and make them remember that this should never happen again.

Because you as a minority could be the next one.

Narrator: Consider this.

Over 110,000 men, women and children of Japanese ancestry were relocated to facilities all around the West.

The primary reason for the relocation was the government's concerns that these individuals may harbor loyalties to Japan, could spy on its behalf, could commit sabotage on military facilities or could otherwise assist a West Coast invasion.

The relocation of all individuals of Japanese ancestry was deemed necessary because of the presence of an unascertained number of disloyal members of a larger group.

The military authorities argued that it was impossible to bring about an immediate segregation of the disloyal from the loyal.

This was the justification for relocation of all persons of Japanese ancestry, two thirds of whom were women and children.

But recently released information shows that there was no evidence that any individual of Japanese ancestry attempted to spy for Japan or committed acts of sabotage.

In fact, during the entire war, only ten people were convicted of spying for Japan.

All were Caucasian.

[Applause] [Music]

Preview of "The Nisei Paradox: Justice on Trial"

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S8 Ep1 | 30s | A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII. (30s)

Introduction to "The Nisei Paradox: Justice on Trial"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep1 | 12m 33s | A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII. (12m 33s)

Tease to "The Nisei Paradox: Justice on Trial"

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S8 Ep1 | 1m 10s | A retelling of the case of Japanese American men who resisted government conscription during WWII. (1m 10s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Idaho Experience is a local public television program presented by IdahoPTV

Major funding for Idaho Experience provided by the James and Barbara Cimino Foundation, Anne Voillequé and Louise Nelson, Judy and Steve Meyer. Additional funding by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson...